By John Gruber

npx workos: An AI agent that writes auth directly into your codebase.

Going Dutch

Monday, 7 February 2022

The continuing saga of Apple’s conflict with the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) — the Dutch equivalent of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission — is fascinating. But I’m finding it hard to write about cohesively, because it’s hard to intertwine an explanation of what is going on with what those of us with opinions on the matter think should be going on. So, let’s shoot here for a discussion merely of what is going on, and put (most) judgments aside for later.

Apple Meant It

On Friday, Apple updated its “Distributing Dating Apps in the Netherlands” developer documentation, which now includes a description of how Apple intends to get paid for purchases in apps that choose to use alternate in-app payment processing or links to websites:

Consistent with the ACM’s order, dating apps that are granted an entitlement to link out or use a third-party in-app payment provider will pay Apple a commission on transactions. Apple will charge a 27% commission on the price paid by the user, net of value-added taxes. This is a reduced rate that excludes value related to payment processing and related activities. Developers will be responsible for the collection and remittance of any applicable taxes, such as the Netherlands’ value-added tax (VAT), for sales processed by a third-party payment provider.

Developers using these entitlements will be required to provide a report to Apple recording each sale of digital goods and content that has been facilitated through the App Store. This report will need to be provided monthly within 15 calendar days following the end of Apple’s fiscal month. To learn about the details that will need to be included in the report, view an example report. Qualifying developers will receive an invoice based on the reporting and will be required to remit payment to Apple for the amount invoiced within 45 days following the end of Apple’s fiscal month. In the future, if Apple develops technical solutions to facilitate reporting, developers will be required to adopt such technologies.

Please note that Apple has audit rights pursuant to the entitlement’s terms and conditions. This will allow Apple to review the accuracy of a developer’s record of digital transactions as a result of the entitlement, ensuring the appropriate commission has been paid to Apple. Failure to pay Apple’s commission could result in the offset of proceeds owed to you in other markets, removal of your app from the App Store or removal from the Apple Developer program.

I don’t know why anyone is surprised by this, but some are. Apple has been clear from the App Store’s debut that their cut from App Store sales wasn’t merely for payment processing. The 70/30 split is the same as the split from the iTunes Music Store, and no one ever claimed that was for “payment processing” alone. Apple sees the App Store as a store, and the entire iOS third-party ecosystem as an extension of that store, and expects a retailer’s cut of sales.

Testifying during the Epic trial last May, Tim Cook made that clear. From iMore’s coverage of his testimony:

Asked about the prospect of letting developers use their own in-app payment systems (as opposed to Apple’s in-app payment system) Cook stated:

“It would wind up where customers would then have to fill in their credit cards for all of these different apps, so it would be a huge convenience issue, but also the fraud issues would go up...”

Then Cook dropped a bombshell:

“Also, we would have to come up with an alternate way of collecting our commission. We would then have to figure out how to track what’s going on and invoice it and then chase the developers. It seems like a process that doesn’t need to exist”.

See also this brief from Apple’s attorneys filed on 30 November 2021 (page 10, some legal citations omitted for clarity):

Finally, Epic suggests that “Apple will not receive a commission” on “transactions that happen outside the app, ... on which Apple has never charged a commission.” That is not correct. Apple has not previously charged a commission on purchases of digital content via buttons and links because such purchases have not been permitted. If the injunction were to go into effect, Apple could charge a commission on purchases made through such mechanisms. See Ex. A, at 67 (“Under all [e-commerce] models, Apple would be entitled to a commission or licensing fee, even if IAP was optional”). Apple would have to create a system and process for doing so; but because Apple could not recoup those expenditures (of time and resources) from Epic even after prevailing on appeal, the injunction would impose irreparable injury. Moreover, an alternative commission structure could have indirect network effects on both sides of the App Store platform.

Apple’s lawyers said Apple could charge a commission on such purchases, but lawyers are going to lawyer. Cook, in his testimony, made clear that Apple would. And so they are. I often compare Apple punditry to Kremlinology — to predict or analyze an opaque, secretive organization, you’ve got to read between the lines of the few things they do say, and you’ve got to know how to interpret silence. The “interpreting silence” aspect is the hard part; what Apple does say they almost always mean. Just listen to them.1 When they said they would devise a way to collect their 15 to 30 percent commissions on App Store transactions for digital goods, they meant it.

Apple’s New Proposal Is Seemingly Not Compliant With What the ACM Has Already Ordered

The strangest aspect of Apple’s new guidelines is that they’re intended specifically and solely to address the ACM requirements, and we already know they do not. I think? Apple’s guidelines seem so contradictory with the ACM’s requirements that I feel like I must be missing something.

On January 24 — 11 days prior to Apple’s publication of these updated guidelines — the ACM issued this:

In addition, Apple has raised several barriers for dating-app providers to the use of third-party payment systems. That, too, is at odds with ACM’s requirements. For example, Apple seemingly forces app providers to make a choice: either refer to payment systems outside of the app or to an alternative payment system. That is not allowed. Providers must be able to choose both options.

Apple’s new guidelines state, in the very first paragraph (emphasis added):

To comply with an order from the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM), Apple allows developers distributing dating apps on the Netherlands App Store to choose to do one of the following: 1) continue using Apple’s in-app purchase system, 2) use a third-party payment system within the app, or 3) include an in-app link directing users to the developer’s website to complete a purchase.

Neither the ACM ruling nor Apple’s updated guidelines seem ambiguous here, but clearly Apple’s guidelines don’t comply with “Providers must be able to choose both options.”

I can only presume that Apple’s new guidelines don’t yet reflect the ACM’s January 24 ruling, but it seems odd, to say the least, to publish them last week anyway.

Apple and Google’s Different Takes

Speaking of giving developers a choice to provide multiple payment options within their apps, it’s interesting to contrast Apple’s intentions with Google’s. For compliance with new regulations in South Korea, Google announced a similar plan in early November for allowing alternate payment services in Play Store apps, reducing their “service fee” by 4 percent.

What’s interesting to me is that in Google’s proposal for South Korea, apps choosing to offer their own payment processing must offer it as a choice alongside the Play Store’s built-in in-app purchasing. In Apple’s proposal for dating apps in the Netherlands, developers must make an exclusive choice: use Apple’s IAP, or provide their own payment processing in-app, or link users to a payment page on the web.

Both Apple and Google obviously want purchases to be made using their built-in purchasing. Google’s thinking seems to be that if third-party payment options can only be offered alongside their built-in Play Store processing, most users will just use the Play Store option. Apple’s thinking seems to be to make offering third-party payment processing so unappealing to developers (including the requirement that they use an entirely different SKU just for the Netherlands version of their app) that they won’t even bother.

Google’s take strikes me as more likely to fly with these regulators.

A 3 Percent Commission Reduction Is Spitefully Small

The reduced commission rate of 27% isn’t completely arbitrary — clearly it’s based on a rough estimate of 3% for payment processing fees. But 3% isn’t enough to cover most developers’ actual payment processing. Google, in their aforementioned response to new regulations in South Korea, is reducing their commission by 4% for Play Store developers choosing to process payments through a third party, and even that is not enough to cover actual payment processing costs in most cases.

Consider Stripe, which is incredibly popular (and deservedly so). Stripe charges 2.9% plus $0.30 per transaction. That’s very fair and delightfully simple, but while that extra 30 cents per transaction is negligible for large transactions, for small ones, it’s very significant. Consider a $10 in-app purchase or monthly subscription charge. Through Stripe, that would incur $0.59 in fees — effectively 6%.

The whole reason many developers wish they could process their own payments in-app is to pay less in overall fees; with Apple’s proposed policy for dating apps in the Netherlands, they’d wind up paying more — Apple’s 27% commission plus at least 5–6% to their payment processor.

If I were at Apple, I’d have pushed to reduce the commission for these apps to 25% — which in addition to being a nice round number, would come closer to break-even with real-world payment processing costs.

The Required In-App Modal Warning

Apple’s new guidelines require a modal warning sheet before an app can direct a user to make a purchase or enter any payment information. The design and language of these warning sheets “must exactly match” Apple’s specifications. Apple provides both English and Dutch messaging. The English version reads:

Title: This app does not support the App Store’s private and secure payment system

Body: All purchases in the <App Name> app will be managed by the developer “<Developer Name>.” Your stored App Store payment method and related features, such as subscription management and refund requests, will not be available. Only purchases through the App Store are secured by Apple.

Learn More

Action 1: Continue

Action 2: Cancel

That’s the warning sheet for apps providing their own in-app payment processing; there’s a similar required warning sheet for apps that link users to the web to make payments. The language here is clearly slanted — perhaps laughably so. The title, for example, sort of implies that only Apple’s payment system is “private and secure”. I do think there should be some sort of required notice before users are presented with non-App Store payments — users might justifiably assume that all in-app purchases go through Apple’s system, because heretofore they did — but the language ought to be fair. “Fair” is obviously in the mind of the beholder, but a good rule of thumb might be that the language should read as though it were jointly agreed upon by both Apple and the developer presenting the warning. As written, these warnings make Apple look petulant. (Which I suppose is accurate.)

It is unclear to me whether Apple intends to require developers to present these warning sheets each time users make an in-app purchase, or just once. It is also unstated in the guidelines what should happen when a user taps the “Learn More” link.

These “roll your own sheets, but follow our specifications exactly” warnings are stopgap measures. Apple’s guidelines state:

Apple is developing a new StoreKit External Purchase API that will provide the in-app modal sheet that informs users of an external payment system prior to a payment flow. The API will also include the functionality of Storefront or SKStorefront.

When the new StoreKit External Purchase API becomes available, you must adopt it by submitting the next update of your app within 30 days. You’ll need to use the in-app modal sheet provided by the API. Your app will also need to continue calling SKStorefront or Storefront prior to every instance of making a purchase or entering payment information, unless it’s an instance in which your app calls the StoreKit External Purchase API.

It’s possible that Apple’s forthcoming APIs for using these entitlements will track purchasing intent, so that developers using them won’t need to file manual sales reports with Apple, but that’s purely speculation on my part.

The ACM Ruling’s Specificity Is Weird

It’s complicated enough for regulations to be enacted piecemeal, country-by-country (and perhaps within countries, state-by-state) around the world. But the Netherlands ACM ruling is really weird in that it only applies to dating apps. This makes no sense to me and I’ve never seen a good argument from anyone why dating apps deserve any sort of special treatment.2

We do know that the ACM inquiry started after a complaint by Match Group, the parent company that now owns what I believe to be a majority of the world’s most popular dating apps. But all sorts of companies seeking to loosen Apple and Google’s control over their respective app stores have petitioned regulators around the world. Spotify and Epic Games, for example. Why the ACM issued a ruling specifically focused on dating apps is baffling to me, other than that it’s the output of a stringent bureaucracy — in response to a petition from the maker of dating apps, they can only issue a ruling that affects dating apps, even if the logic is more widely applicable.

Here’s how the ACM’s own ruling (PDF) justifies it:

This decision concerns dating-app providers that offer apps in the App Store. For these providers, offering an app is critical since consumers use dating services primarily on their smart mobile devices, and consumers prefer using apps: apps are appealing because, in that way, several functionalities specific to smart mobile devices can be used that are available in apps, but that are not available (or available to a lesser degree) on mobile websites. For example, think of push notifications, data storage, GPS, the speed of the service. For dating app, [sic] this is very important.

Virtually all dating-app providers use a business model (the freemium model) in which they offer the app for free in the App Store, and subsequently generate revenue by offering premium functionalities, content, and services within the app. This often concerns combinations of subscriptions and expendable items (such as likes and superlikes). For these services within the app, dating-app providers are required to use Apple’s payment system, and comply with Apple’s additional conditions.

Push notifications remain unavailable to websites on iOS (but perhaps they’re coming soon-ish?), but GPS and local storage are available to web apps. (You can use Apple Maps from DuckDuckGo search results, if you want to try it.) But rather than argue specifics, what the ACM is saying here is something we all know to be true: native apps are better and more popular with users than websites and web apps on mobile phones. What’s interesting about this argument is that it can be used both ways. The ACM is saying “The native app experience is better so dating apps need to be native apps to be competitive”, but Apple’s implicit argument is “We agree the native experience is superior, and we created it, which is why we deserve to profit from it”.

I know I wrote up front that I was going to avoid making judgments about what should be done, but this ACM ruling’s sole focus on “dating apps” is downright absurd. There are a lot of other classes of app where being native is more essential than it is for dating apps. Just off the top of my head: camera apps (especially video) and games. And there are apps like VPNs that literally can’t work as web apps — they have to be native, and thus on iOS, have to go through the App Store.

I’m not being coy here. I get it that proponents of the ACM’s ruling see the “just dating apps” specificity as a mere foot in the door. First dating apps, then more classes of apps, then all apps. Something like that. But laws, regulations, and rules in general should make sense every step of the way. Right now, the ACM’s sole focus on dating apps makes no sense.

Compare and contrast with the Japan Fair Trade Commission’s investigation into “reader” apps, which Apple settled in September by agreeing to allow such apps to link out to the web. That’s a carveout for a specific class of apps that makes sense. (Apple: “Reader apps provide previously purchased content or content subscriptions for digital magazines, newspapers, books, audio, music, and video.”)

[Update: Here’s a post on the Dutch site Tweakers (Google translation to English) that claims the ACM has conducted research that shows “that dating app providers suffer the most from these conditions”, where “these conditions” refers to the iPhone/Android duopoly and the need for dating apps to be on both platforms. Doesn’t seem compelling to me.]

Apple Intends to Collect Its Commission for Payments Made on the Web

Speaking of Apple’s agreement with the Japan Fair Trade Commission, my assumption (and the assumption of most people, I think) has been that when this change goes into effect (“in early 2022”, says Apple’s September announcement), reader apps that link to their websites for payments, purchases, and account creation will pay Apple nothing for those transactions. Now, though, seeing that Apple intends to collect its commission from dating apps in the Netherlands that choose to link to the web for payment processing, I’m not so sure.

I still think Apple intends to put into effect one new global policy for “reader” apps — wherein Apple collects no commission from purchases and subscriptions placed on the web — and this entirely separate policy for dating apps in the Netherlands. We shall see.

There’s some inherent ambiguity to Apple’s intention to collect a commission on payments made on the web. What happens if a user taps “Continue” to open a dating service’s website in their browser, then they close the browser tab, but then subsequently go back to the dating service’s website on their own, and sign up for a subscription or make a purchase — possibly from a different (non-iOS) device? Does Apple think the dating service still owes them a commission on that purchase? That seems both crazy and unenforceable.

It strikes me as inherently problematic for Apple to demand anything from transactions that take place outside the app. In-app is a clear distinction, whether payments are processed with Apple’s own system or a third-party payment provider. That’s why I think it’s a good rule that web links must take users to a tab in their default web browser, and can’t use an in-app web view. It makes the distinction clear. Laying claim to a commission on transactions outside the app, even if they were initiated by tapping a button in the app, seems impossible to adjudicate.

No URL Parameters Allowed

Another restriction on web-based payments: an app can only have one URL that users are sent to, and that URL cannot contain any parameters:

The link must:

- Surface the External Purchase Link Modal Sheet (Figure 2), explaining that the user is leaving the app and going to the web to make purchases through a source other than Apple;

- Open a new window in the default browser installed on the user’s device; the link may not open a web view in the app;

- Not pass additional parameters in the URL, so that user or device data is not transmitted to the developer without the user’s knowledge or permission;

- Go directly to your website without any redirect or intermediate link or landing page;

- Appear only once per app page, and must display the same message in each instance; and

- Be submitted with your app to App Review, and be resubmitted if the URL changes.

I doubt it’s a dealbreaker that the URL cannot contain parameters, but it does seem overly restrictive. One natural parameter to a payment URL would be an identifier for what it is the user intends to purchase. Apple justifies this restriction “so that user or device data is not transmitted to the developer without the user’s knowledge or permission”, but they are also requiring that the app present the user with a modal warning dialog before they are redirected to the web. The app could get explicit permission for passing along “user or device data” in URL parameters in the mandatory confirmation sheet — with a detailed explanation in that sheet regarding what is being shared.

Here We Are

I don’t know how much of the current animosity, controversy, and regulatory scrutiny would have been avoided if Apple had, as the App Store grew, dialed back the revenue split to 75/25 and eventually 80/20, but it would have done something. But here we are.

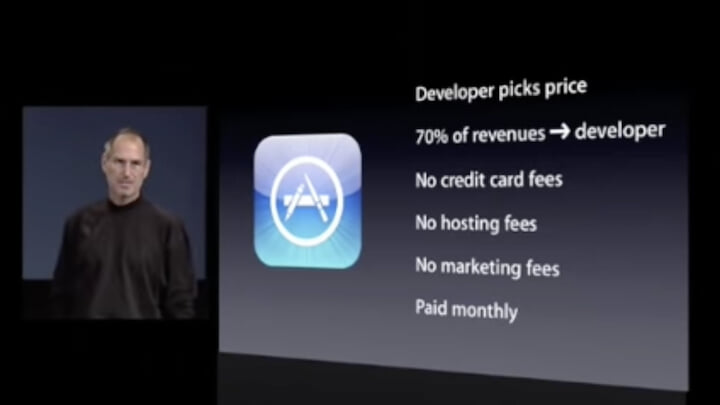

Here’s the slide from Steve Jobs’s March 2008 introduction of the App Store showing “the deal”, as he put it:

Comparisons to the mobile software market of 2008 feel like ancient history — iOS and Android have completely redefined that world. There’s also a mismatch between Apple’s original conception of the App Store and our understanding today. When the App Store debuted there were free apps and paid-up-front apps, and that was it — no in-app purchases, no subscriptions. When Apple first added in-app purchases, they were only available to paid apps — free apps couldn’t offer them. Today, almost all revenue in the App Store comes from in-app purchases and subscriptions in free-to-download apps (games in particular). Paying for an app up front, before you can even download it, feels more like a traditional “store”. Paying for stuff in an app, after you’ve installed it, feels more like something else.

That slide above still looks like a good deal when compared to dedicated gaming platforms like Switch, PlayStation, and Xbox. It looks punitive, though, compared to install-whatever-you-want-from-wherever-you-want platforms like Windows and MacOS. It’s a matter of perspective, and while Apple’s perspective has been very consistent through the entirety of the iPhone era, they have conspicuously not explained their perspective as times have changed and as the platform has grown to half of a global duopoly. To wit, that Apple is justified in charging a 15–30 percent commission on App Store transactions for digital purchases, and has earned the profits that ensue from that commission.

It’s obvious many developers wrongly assumed that Apple’s commissions were for payment processing alone. Were regulators like the Dutch ACM similarly wrong? Is the point of the ACM’s ruling merely that dating apps should have the option of processing payments however they choose, while paying the same effective commission to Apple? Or was their intention to provide dating apps the option to process payments on their own to avoid Apple’s commission? I know a lot of people reading this are going to think “Of course their intention was to allow developers to avoid Apple’s commission!” They feel so strongly against Apple’s App Store commission that even their thoughts have exclamation marks. But give the ACM’s ruling a close read — they don’t make that argument at all.

But whatever one thinks of the ACM’s ruling, clearly they intended their new regulations to offer dating app developers options that they might want to actually use. Apple’s guidelines for complying with the ACM ruling offer options so unappealing — higher overall commission payments, arduous accounting rules for reporting sales to Apple, a mandatory warning to users that paints non-Apple payment systems as unsafe, requiring separate Netherlands-specific App Store versions for apps using these new entitlements — that I question whether any developers will choose to use them. (It would be amusing, to say the least, if Apple’s new guidelines stand and even the Match Group doesn’t use them for their dating apps in the Netherlands.)

The Dutch ACM already slapped Apple’s hand for non-compliance before these updated guidelines were published. What does Apple think the ACM is going to do now that they have been published, and explicitly contradict the ACM’s seemingly clear intentions? Rather than decrease regulatory tensions, Apple’s new guidelines seem to intentionally escalate them.

-

Steve Jobs would often say things he didn’t mean. To pick just one example, in 2004 he repeatedly said that Apple wasn’t working on a video iPod, because no one would want to watch video on such a small display. A year later they introduced an iPod that played video on a screen that exact size, and in 2007 released a video-capable iPod Nano with an even smaller screen. That was a Jobs thing — his famed reality distortion field — not an Apple thing. Cook is a much straighter shooter and Apple today reflects that. ↩︎

-

Paragraph 16 of the ACM’s original ruling (PDF) does state, “In addition, it becomes much harder for dating-app providers to do background checks, which is of significant importance to dating-app providers, considering safety, age checks, and malevolent users.” But this is less about who is processing payments and more about Apple’s privacy restrictions for apps in general. And in the real world, it does not seem like iOS dating apps are problematic in this regard. There’s also this tweet from the ACM (!), earlier today, which states “People don’t date from behind the desktop computer” and that’s about as clear as it gets. ↩︎︎