By John Gruber

Sentry — Catch, trace,

and fix bugs across your entire stack.

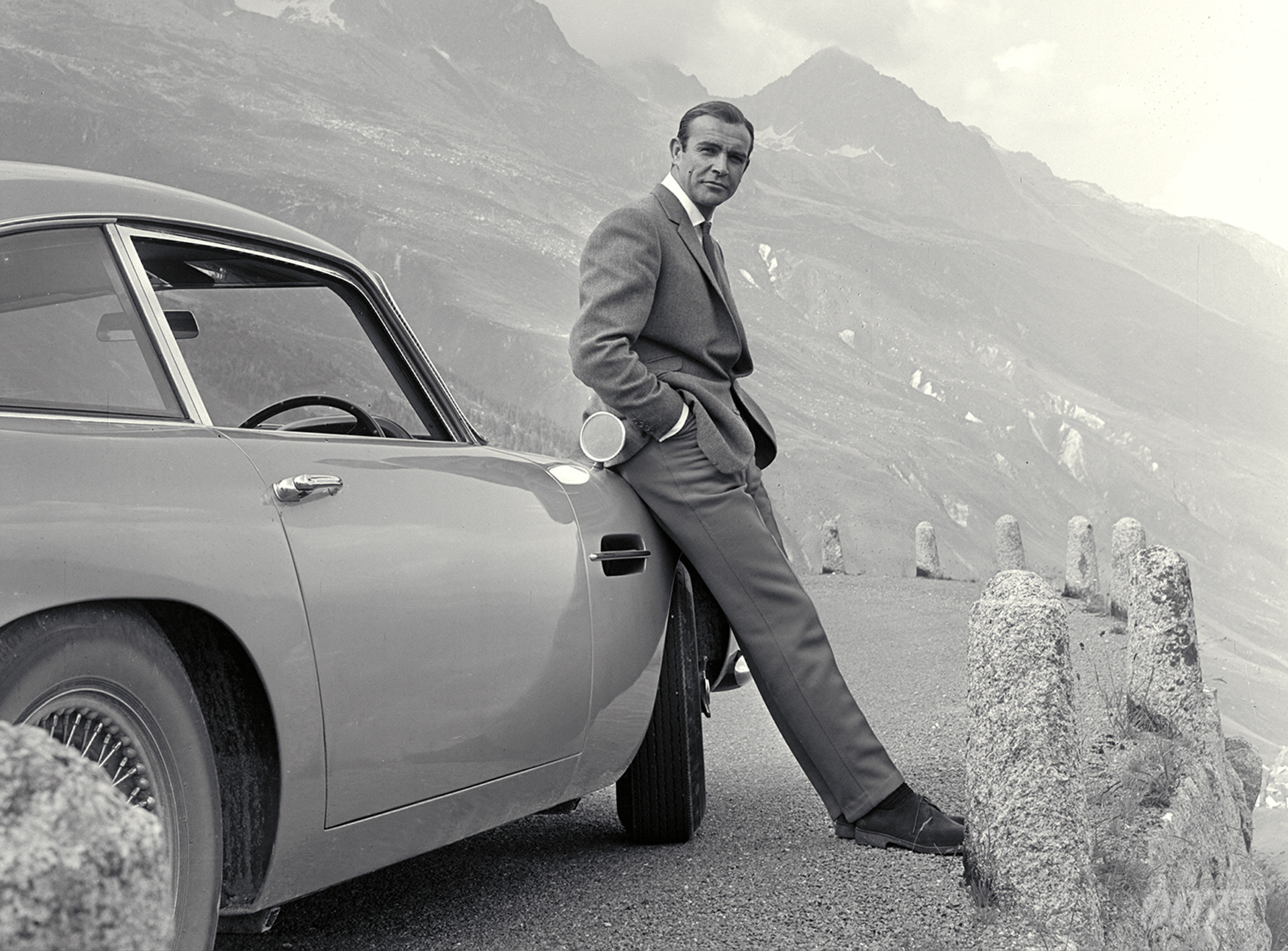

Sean Connery

Saturday, 31 October 2020

Aljean Harmetz, for The New York Times:

Sean Connery, the irascible Scot from the slums of Edinburgh who found international fame as Hollywood’s original James Bond, dismayed his fans by walking away from the Bond franchise and went on to have a long and fruitful career as a respected actor and an always bankable star, died on Saturday in Nassau, the Bahamas. He was 90. […]

“Nonprofessionals just didn’t realize what superb high-comedy acting that Bond role was,” Mr. Lumet once said. “It was like what they used to say about Cary Grant. ‘Oh,’ they’d say, ‘he’s just got charm.’ Well, first of all, charm is actually not all that easy a quality to come by. And what they overlooked in both Cary Grant and Sean was their enormous skill.”

Connery’s Bond movies speak for themselves, but you could fill an entire film festival with his other work. His films with Lumet were terrific (I’m particularly partial to The Anderson Tapes.) From his later career, consider just John McTiernan’s The Hunt for Red October and Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and The Last Crusade. Indelible roles working with great directors. And, of course, Brian De Palma’s masterpiece, The Untouchables:

Mr. Connery taught himself to understand that character — Jim Malone, a cynical, streetwise police officer whose only goal is to be alive at the end of his shift — by noting the other characters’ attitudes toward him. After reading Malone’s scenes, he told The Times in 1987, he read the scenes in which his character did not appear. “That way,” he said, “I get to know what the character is aware of and, more importantly, what he is not aware of. The trap that bad actors fall into is playing information they don’t have.”

That dynamic is what elevated The Untouchables. Kevin Costner’s Eliot Ness never wavers in his belief that they’re going to get Al Capone. Connery’s Jim Malone thinks they won’t, it’s futile, but it’s worth trying anyway because that’s what you do: you do the right thing as best you can.

And that, to me, was part of the genius of Connery’s Bond. When he’s strapped to that board in Goldfinger (“Do you expect me to talk?” “No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die.”) the whole situation is contrived as hell but Connery makes you believe that he’s a man who thinks he’s about to be killed, crotch first, by a goddamn laser.

Roger Moore’s keen insight when he took over the role was not to play Bond as a different character, per se, but to play it an entirely different way. And that idea of playing to information the character doesn’t have exemplifies it. Moore’s Bond winkingly knew what the audience knew — that the last page of the script had the world saved and Bond in embrace with the girl. Connery’s Bond felt like he didn’t know if he’d survive to the next scene — that every fight might be his last. That, combined with his effervescent cool, is what instills those movies with staying power.