By John Gruber

Finalist Day Planner:

Made for your Dock

Wavelength

Monday, 27 March 2023

In September 2020, a new social network named Telepath launched. I had been beta-testing it for over a year before it debuted, at the invitation of Marc Bodnick, one of Telepath’s co-founders and a Quora alum. My first impression, in a DM exchange with Bodnick in May 2019, was that Telepath struck me as “something like Twitter but with real names and enforced civility, and with hashtags as Slack-like channels of interest.” Bodnick’s reply: “Yeah, in so many words.”

Good coverage from Telepath’s 2020 launch: Biz Carson at Protocol, Casey Newton at The Verge, and Sarah Perez at TechCrunch. I liked the concept, and I really liked Telepath’s design: clear, attractive, distinctive, iOS native. I wanted to like it. It seemed like something I should have liked. But a certain je ne sais quoi just wasn’t there. Something fundamental about Telepath just never clicked for me.

Perhaps my je ne sais quoi spidey-sense remains well tuned: Telepath never really took off. There’s a good chance you don’t recall ever hearing about Telepath.

Then last June, Bodnick reached out to me again, asking if I’d be interested in something new from the same team: Wavelength, a group messaging app focused on privacy and intuitive threading, and which integrates GPT-3.5 AI chat into group discussions. The Telepath DNA was obvious: good design, idiomatically native to iOS, and the groups I joined all had very high signal-to-noise ratios. That’s no surprise: their team is small, with just two developers and fellow co-founders: Richard Henry and Riley Patterson. Wavelength immediately felt like a new band from the same musicians. And this time, something did click. The je ne sais quoi was there. I felt certain they were onto something with Wavelength.

In August the company announced they were shutting down the Telepath app, and shifting their entire focus to Wavelength. This announcement was so low on hype that Casey Newton simply published a short statement from the team on Twitter:

We’re shifting our focus to private group chat because it’s incredibly fun and we love it, and also because it sucks. The world has been moving from public spaces into messaging apps, and I think many of us are feeling the strain of these products. Group chats get noisy really quickly, and you can only talk about a single thing at a time without derailing everything. If a conversation is noisy, the only option is to mute the entire group. On Wavelength you can mute a thread about a basketball game you’re not interested in, while staying looped in on another thread about dinner plans for tonight.

Messages on Wavelength are completely private and secure, using state of the art end-to-end encryption. It also includes an optional message history sync feature; this means that when new members are invited to a group, the existing members can automatically re-encrypt and securely send the recent message history — which is important for threaded chat, so that conversations aren’t broken. This is the first time that an end-to-end encrypted messaging app has a feature like this.

I’ve quoted Bodnick’s statement in its entirety because it remains a perfect description of Wavelength. I can’t say what it was about Telepath that didn’t click for me. I don’t know why I can’t, but I can’t. But I can say why Wavelength does click for me.

One of my strongest product design beliefs is that it matters, greatly, where you start conceptually. Every successful software platform evolves, but its origin, the core, pervades forever. Personal messaging apps like WhatsApp, Signal, and Apple’s Messages all support group chats. But they are fundamentally apps for one-on-one messaging, with group chat added on. Messages is by far my most-used messaging app, but I’m active, weekly if not daily, on Signal and WhatsApp too. All three feel most natural in one-on-one chats, and with groups small enough such that the members could all fit in an SUV or minivan. If you can’t count the members of a group chat in those apps on a single hand, it’s probably an unwieldy group. I have never been in a group chat in such apps with more than 10 participants, nor in a group where I don’t somehow know each of the participants. Group chats in such apps aren’t just private, they’re personal.

Messages, Signal, WhatsApp, and their cohorts all share the same fundamental two-level design: a list of chats, and a single thread of messages within each chat. This is the obvious and correct design for a messaging app whose primary focus is one-on-one personal chats. Group chats, in these apps, work best the closer they are in membership to one-on-one.

Wavelength is different because it’s group-first. This manifests conceptually by adding a third, middle level to the design: threads. At the root level of Wavelength are groups. Groups have an owner, and members. At the second level are threads. Inside threads, of course, are the actual messages.

Messages / Signal / WhatsApp, conceptually:

Groups → One thread of all messages for that group

Wavelength:

Groups → Threads → Messages for each thread

The difference made by adding threads as an additional hierarchical layer is so simple to understand that it feels obvious, not designed per se but merely discovered. But the difference is profound.

The other difference that being group-first makes is that while every group in Wavelength is private, they’re not necessarily personal. I’m an active participant in several groups with hundreds of members, and even some of the smaller groups I’ve been invited to include people whom I don’t know personally. That’d be weird in Messages. It’s perfectly natural in Wavelength. One way to think about it is that while Wavelength itself is not a social network, it’s a platform that lets you create your own private micro social networks in the form of groups. If you’re old enough, you can draw an analogy to the heyday of Usenet — Wavelength groups feel a bit like Usenet groups, if Usenet groups had been private.

You only join groups that interest you. You only pay attention to threads within the group that interest you. The result feels natural and profoundly efficient in terms of your attention and time.

Earlier this year, Bodnick let me know that Wavelength would soon be moving out of TestFlight invitation-only testing and opening up, quietly but not secretly, via public distribution on the App Store.1 This made sense to me — I’d been using Wavelength almost daily since June. It was good from my start with it and was constantly getting better. I agreed it felt like time to expand — both because the app was good enough to justify expanding, and because Wavelength needed the feedback and perspective from a wider and more diverse base of users.

But there had always been something about Wavelength that didn’t sit right with me. The top-level list of groups was great. The bottom-level list of messages within a thread was good. (At the time it sorely needed a better indication of which messages were new to you, but I knew they were working on that.) But the middle level, the list of threads within a group, was wrongly designed.

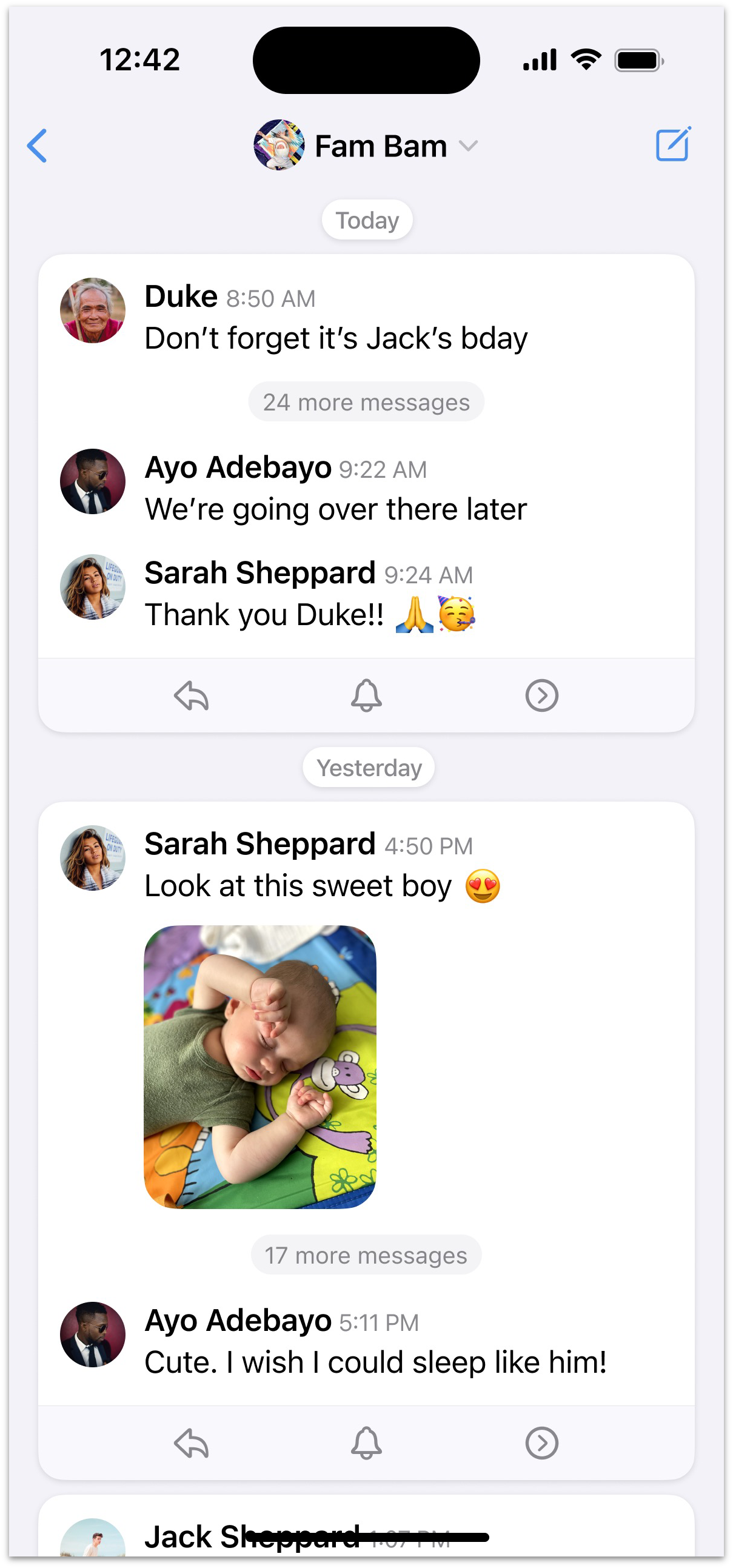

What they had for that list of threads was a clever idea. For each thread, Wavelength presented a sort-of card, with the first message in the thread at the top, and the most recent message or two in the thread at the bottom, and between them, an indicator showing how many other messages were in the thread, between the first message and the last one or two that were shown in the card. “4 more messages”, “26 more messages”, etc. Here’s a screenshot from that thread list design:

That’s attractive, and conceptually it makes obvious sense. Here’s a thread, with the first message at the top, the most recent message at the bottom, and an indicator of how many total messages are in the thread between them. In the abstract there’s nothing wrong with this design, and as I already said, it’s clever and original. In promotional screenshots like the one above, it looks like a design that works. But in practice it was clumsy and frustrating. Showing the most recent message in a thread often, if not usually, made no sense without having read the new-to-you messages in the middle. The best active groups have multiple new threads regularly, and good threads have dozens of messages. “X more messages” really only works if X is a very small number, but X is seldom a small number in a good discussion.

So this threads-as-cards presentation wasn’t useful, and it consumed a tremendous amount of screen real estate for each thread. Objectively, it provided low information density with no practical upside. Subjectively, it made catching up on the threads within a group feel like a chore — like pedalling a bike uphill, rather than coasting downhill. Not a steep incline, but an uphill incline nonetheless.

Presentation-wise, this thread view was the most original thing in Wavelength, and I felt certain they ought to throw it out.2 That’s hard advice to deliver. But if I were on the team, that’s the sort of feedback I’d want to hear — especially because I wasn’t just convinced that I could describe what was wrong, but that I could see what they should do instead: show threads like Apple Mail displays email threads — as a simple list of subjects, with a snippet of the first message, and a blue dot to indicate a thread that contains new messages. So, I wrote up my thoughts and advice, in detail, and sent it to Marc and Richard.

I’m glad I did.

Not only was my feedback warmly received, it begat a series of discussions that culminated in my gladly accepting a position as an official adviser to the company, in exchange for a small amount of equity. I’m happy to disclose this now, and will continue to disclose it when writing about Wavelength henceforth.

In the early years of writing Daring Fireball I needed outside work to make a living, and a decade ago I co-created the late great notes app Vesper with my friends Brent Simmons and Dave Wiskus. But I’ve never before taken an official advisory position like this before. You should take this as a sign of my deep enthusiasm for Wavelength. It is very good right now, and getting better quickly.

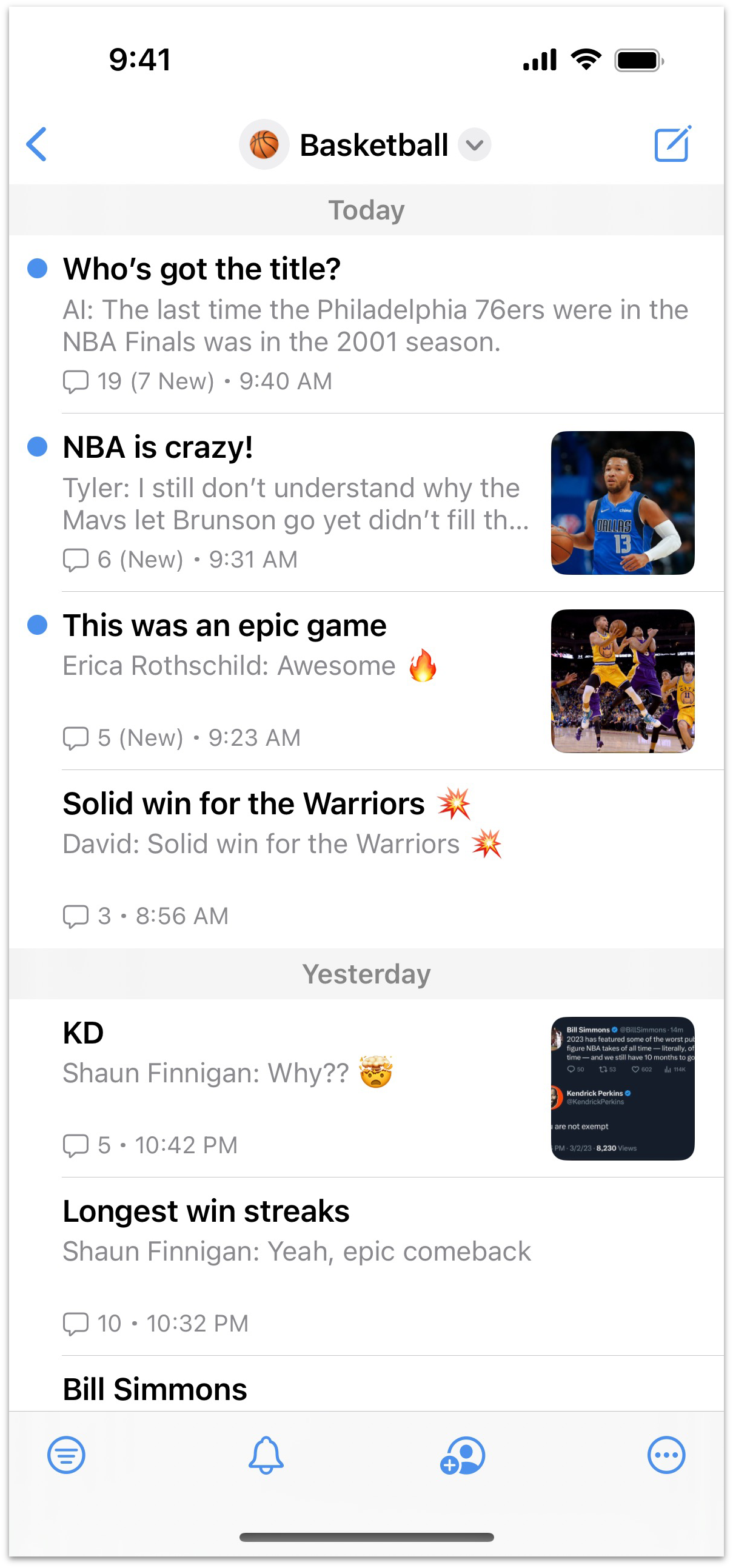

And here’s what Wavelength’s thread view looks like now:

A high-information-density list of threads. Each row in the list has a clear visual hierarchy: subject in bold, a blue “new messages” indicator dot, the name of the thread’s creator, a thumbnail of an image in the first message (if any), a short preview of the first message, the counts for total and unread messages in the thread, and the time of the latest message. There are subtle separators between threads to mark days. That’s it. It’s so obvious that it seems not designed at all, but this view looked very different just a few months ago.

AI Chat Is Fascinating in a Group Context

Broadly speaking, the team behind Wavelength has been on a continuous four-year journey that started with Telepath and evolved into Wavelength. The best parts of Telepath — the focus on privacy, high-quality discourse, and topic-based groups — work better for more people in a chat app than a social network.

In one sense, though, their timing was almost comically bad: they officially pivoted away from Telepath, a Twitter-like social network focused on civility, just a few months before Twitter’s descent into incivility under Elon Musk’s ownership prompted an exodus of users to Twitter alternatives, primarily Mastodon. But Mastodon, and the concept of open federation, is a better solution for civil social networking than any private platform could be. I don’t think Telepath, if they’d stuck with it, was any more likely to out-Mastodon Mastodon than it was to out-Twitter Twitter.

But in a more important sense, Wavelength’s timing feels incredibly serendipitous, because its rollout coincides with the arrival of genuinely useful AI chat. Wavelength’s GPT-3.5 AI integration is trendy, yes, but not all trends are fads. Some are enduring. Bill Gates is placing the arrival of AI on the same level as the graphical user interface, the internet, and mobile phones. That feels right to me.

Wavelength was conceived for human group chat. But when OpenAI’s chat appeared a few months ago, the team realized they’d built the perfect platform and interface for it. A good chat interface is a good chat interface, whether it’s a human on the other end or an AI construct. And the best chat interfaces are in dedicated chat apps — not web browser tabs. The proof of that is in the immense worldwide popularity of dedicated chat apps. There’s no reason to silo AI chat away from human chat. And Wavelength’s focus on threading fits terrifically with AI. You can have one thread where you’re getting help with a programming task like writing a Python script, and a separate thread where you’re spitballing with the AI to suggest names for a new product. Both threads maintain their own contextual history.

And the biggest thing is that interacting with AI chat in a group of people is a different experience from one-on-one AI chat. Group chat with an AI bot as a member is both fun and useful. The Wavelength team has a slew of ideas for where to take AI integration going forward (e.g. persona customization), but as it stands today, it’s already hard for me to imagine launching Wavelength without it.

AI integration is a recent addition to Wavelength, but I’d argue it’s the number one reason to try the app. It’s “AI with friends” — and no other group messaging platform has this yet.

Why I Think Wavelength Is Worth My Time as an Adviser and, More Importantly, Your Attention as a Potential User

I mentioned personal messaging apps like Messages, Signal, and WhatsApp above. At the other extreme of the messaging platform space are apps like Discord, Slack, and Microsoft Teams. I have used Slack, in particular, for a long time. I give Slack grief every chance I get regarding its overall complexity, non-native desktop Mac app, and the non-idiomatic design and organization of its iOS app.3 But Slack is designed to scale to the needs of very large organizations — companies with thousands or even tens of thousands of employees, often with stringent data storage regulations. That’s a really tough problem to solve, and Slack pulls it off. To my knowledge Slack is the best product out there for large enterprises, and whatever product is in second place remains a distant second.

But in the same way that personal messaging apps designed foremost for one-on-one chats don’t scale up to large groups, Slack feels like overkill for smallish groups. At the highest level, switching from one Slack organization to another feels more like switching between apps than switching between groups. I, like many people, tend to call an organization or group’s Slack instance a “slack”, as in, “There’s a good discussion about this feature in the NetNewsWire slack.” At the next hierarchical level, Slack’s channels are the wrong concept for a small group. And “channels” seldom make sense for a fleeting discussion. A small or even medium sized group doesn’t need channels, it just needs threads. And don’t get me started on Slack’s odious threading presentation within channels.

So on one extreme are personal messaging apps that are optimized for one-on-one chats and groups small enough to fit in a van. On the other are enterprise apps like Slack and Teams that are optimized for organizations that could fill a theater or even an arena.

Wavelength is designed for the area between those extremes. Think: groups that could fit in a bus, or even an airplane. I suppose Discord is a competitor, but I find Discord more visually cacophonous than even Slack, and conceptually, Discord is Slack-like, with top-level “servers”, and ugly IRC-style #channels-whose-names-are-lowercase-and-cant-contain-spaces-like-dos-filenames-from-40-fucking-years-ago. Nor is Discord designed with privacy in mind.

Wavelength is the opposite of cacophonous. It’s visually quiet. It looks a lot like what I’d imagine a new “Messages for Groups” app from Apple itself would look like.

What else:

Wavelength is currently available only for iPhone, iPad, and Mac. An Android app is planned (see next item). The iOS app is really good. The Mac app is good too, but not yet really good. It’s built using Catalyst, and some Catalyst-isms still show through. Off the top of my head: scrolling via keyboard shortcuts like the space bar and page up/down keys doesn’t yet work; and it doesn’t respond to commands from the system-wide Services menu.) But these are known issues, and as Wavelength’s Mac app stands today, it’s infinitely better than the Electron web-app-wrappers that attempt to pass as “Mac apps” from most messaging platforms. If not for Wavelength’s obvious commitment to building great modern native apps for both iOS and Mac, I wouldn’t be involved as an adviser, and I likely wouldn’t even be a user. You either get why native apps are essential, experience-wise, or you don’t. The Wavelength team gets it.

As mentioned above, Wavelength’s development team is very small. Two people, Henry and Patterson. That puts a limit on how much they can accomplish — hence the lack of an Android app at the moment. And this makes Wavelength a poster child for why Catalyst exists. Again, Wavelength’s Mac app is good, not great (yet), but likely wouldn’t exist at all if not for Catalyst and the ability to share almost the entirety of its source code between iOS and Mac. But this small team size is also why they can move fast. There is zero bureaucracy, and with their shared experience coming from Telepath, years-long familiarity and camaraderie.

Wavelength’s double ratchet end-to-end encryption game is on-point, and the platform was designed from the ground up with state-of-the-art encryption in mind.

The privacy policy is clear and good. Wavelength’s App Store privacy scorecard is succinct.

When you sign up, Wavelength asks for your phone number. That’s just your identifier. You’re not going to get any phone calls, and Wavelength is never going to sell your number to spammers. In lieu of passwords, when you sign in on a new device, Wavelength sends a confirmation code via SMS. (Support for passkeys and hardware security keys is forthcoming.)

From the department of “If you’re not the customer you’re the product”: Wavelength is free to use and will remain so. There are no ads and there are never going to be ads. (And because of the way the E2E encryption works, it’s not even possible hypothetically to serve algorithmic ads based on message content.) Wavelength plans to make money selling pro features, including, perhaps, a version of Wavelength for organizations.

Wavelength is deceptively simple. You will never get lost. There is a welcome scarcity of settings. But its deceptive simplicity means you can be an active participant (or simply a sideline follower/lurker) in a large number of active groups, each with a large number of active threads, and it never seems overwhelming. I’m active in several groups with hundreds of members. That’s just not feasible in personal messaging apps like Messages or Signal. But I’d never join any of these groups if they were in Slack or Discord. Joining a Wavelength group is no heavier a task nor any more of a commitment than, say, following an RSS feed. Don’t like a group? Just leave.

A key aspect of Wavelength’s utility for following multiple large, active groups are fine-grained, easy and obvious controls for notifications. For each group you join, you can choose to be notified about new messages or not, or to get alerts only for threads in that group in which you’ve posted. And within each group, you can mute individual threads. So if you’re in a group for which you want notifications on by default, but there’s an active thread about something you’re not interested in, you can just mute that thread and continue getting notifications for the other threads in that group. Even for small groups, this is a huge advantage of Wavelength compared to group chats in apps like Messages, Signal, or WhatsApp, which have no concept of threads, which means you can only mute the entire group.

The Chicken and Egg Problem

That’s about it for now. I’ve been a happy Wavelength user for over 9 months now, and I’m proud to be an official adviser to the company. If you’re intrigued, you should download the app and give it a try. But that leads to a bootstrapping dilemma. Wavelength is not a social network. There is no public timeline or directory of public groups. Being the only Wavelength user you know is like being the only WhatsApp or Signal user you know.

One thing you can do solo in Wavelength is converse with the AI, privately via direct message threads. It’s fun and genuinely useful. But it’s a lot more fun with even just one friend in the chat with the AI. Unlike OpenAI’s chat and Google’s just-gone-public Bard, there’s no waiting list for Wavelength. Just install the app, invite a friend or two, and start prompting the AI just by mentioning “@AI” in your groups.

And again: Wavelength is really good at all-human group chat too. So the other thing you can do is spread the word to your friends. Maybe you’re in a group chat in Messages that’s a bit too large or too active for the constraints of a single group thread, and would be better served in Wavelength. Or maybe you’re in a group chat in Slack or Discord where those platforms’ complexity is overkill, and where threads would make more sense than channels. (Or maybe, like me, you just think Slack and Discord are ugly.) It’s worth your while to give Wavelength a look, and bring your friends along.

-

Wavelength’s approach to opening is worth a long story of its own, in my opinion — instead of remaining utterly secret and attempting to explode in popularity with a single big unveiling, they’ve instead eschewed secrecy and opened up to more people slowly and steadily. ↩︎

-

I emphasize “presentation-wise” here because the most innovative aspects of Wavelength are technical, not visual. First: Wavelength’s peer-to-peer history sync for messages in a group uses state-of-the-art end-to-end encryption. No other messaging platform does this, and it works seamlessly. When you join an existing group, old messages and threads populate your view of the group, but those messages aren’t stored on Wavelength’s servers — they come to you from the existing members of the group, and are delivered with cryptographic privacy. Second: integrating ChatGPT-3.5 AI within a group context. No other messaging platform offers this either. ↩︎︎

-

It also annoys me to no end that Slack uses a punctuation-characters-for-text-styling syntax that is Markdown-esque but definitely not Markdown, and they have the temerity to call this Bizarro World syntax “mrkdwn”. ↩︎︎