By John Gruber

Manage GRC Faster with Drata’s Trust Management Platform

The Things They Carried

Monday, 16 September 2024

Thoughts and Observations in the Wake of Apple’s ‘It’s Glowtime’ Keynote

Back in July 2007, I contributed this photo to a Flickr group called, self-describingly, “The Items We Carry”:

17 years later, I’ve consolidated. 2007 was so long ago that Field Notes hadn’t yet been created; my back-pocket notebooks are much slimmer now than that hardcover Moleskine.1 Instead of the Leatherman and a ring of four keys, I’m down to just two keys and a Halifax key-sized tool from The James Brand. The keys and Halifax lay flat and fit comfortably in the change pocket of a pair of jeans.2 And while I do own (and very much enjoy) a Ricoh GR IIIx — a modern but very similarly sized descendant of the above camera — I don’t carry it on an everyday basis because iPhone cameras have gotten so good.

But there was an everyday carry item I omitted from the above photo — wired earbuds. I don’t remember if I omitted them because I forgot to include them, or if it was for aesthetic reasons. But circa 2007 I generally had a pair of wired Apple earbuds with me. Today, I’ve always got my AirPods Pro — far and away my favorite consolidation. By weight, AirPods (with case) are heavier, but measured by fussiness, they offer a never-tangled fraction of the wired earbuds experience.

The remaining items in my pockets are equivalent but upgraded. I’ve got better (and because I no longer wear contact lenses, prescription) sunglasses. I long ago switched from the Pilot G2 to the Zebra Sarasa, a pen I consider nearly perfect. The above Swiss Army watch broke in early 2009, and I’ve since started a small (I swear) collection of mechanical watches. But on most workdays, there’s an Apple Watch on my wrist.

iPhone, AirPods, Apple Watch. I’ve almost always got two of them with me, and often all three. I’m sure for many of you reading this, it’s always all three.

These are Apple’s three “everyday carry” products. They’re as much a part of our lives as our clothes and glasses and jewelry. They thus go together swimmingly in the same product introduction event.

Last week’s “It’s Glowtime” event was very strong for Apple. It might have been the single strongest iPhone event since the introduction of the iPhone X. All three platforms are now in excellent, appealing, and coherent shape:

iPhone: Last year was a bit “meh” for the non-pro iPhone 15 models, which were stuck with year-old A16 silicon and didn’t get the new hardware Action button. This year, the iPhone 16 and 16 Plus get the brand-new A18 chip, the Action button, and the new Camera Control button. That Camera Control button would have made total sense as a Pro-exclusive feature this year (more sense, to me, than making the Action button Pro-exclusive last year) but all new iPhones have it. This year’s iPhone 16 and 16 Plus even come in the best and most fun colors in a few years. The iPhone 16 Pro and 16 Pro Max have best-in-class camera systems, the A18 Pro chip (6 GPUs vs. 5 in the regular A18, bigger CPU caches, faster memory and storage I/O), and slightly bigger screens.3 The iPhone remains the best product in the most important and profitable device category the world has ever seen.

Apple Watch: The new Series 10 models sport bigger displays, longer battery life, and 10 percent reductions in thickness and weight. The new watch displays are slightly bigger, and, more importantly, also have noticeably wider viewing angles, and in always-on mode update once per second instead of once per minute. There’s an absolutely gorgeous polished jet black option in aluminum — marking, to my taste, the first time in the entire history of Apple Watch that there’s a base-priced aluminum model that stands toe-to-toe with the more expensive models on aesthetic grounds. But those more expensive models are better than ever too, with Apple replacing polished stainless steel with much lighter polished titanium. I was unaware that titanium could be polished to a mirror-like sheen. Apple had previously made Series models of Apple Watch in titanium — I bought one in Series 5 and again in Series 7 — but those were at the Edition tier, priced above the stainless steel models. There was no Ultra 3 announcement — the lone sour note in the Watch segment — but the Ultra 2 is now available in an excellent and sure-to-be-popular satin black DLC coating.

AirPods: No more selling years-old models at entry-level prices. The new good/better/best lineup is clear. Good: new AirPods 4 for $129. Better: AirPods 4 with Active Noise Cancellation (ANC) and a better case (with wireless charging and Find My support, including a speaker) for $179. Best: the existing $249 AirPods Pro, which, yes, debuted two years ago, but which continue to be updated with improved functionality via firmware updates — most notably and importantly now, certified support for use as hearing aids. There’s also the revised AirPods Max, with new colors and USB-C replacing Lightning, but alas, no significant internal updates like the H2 chip now available in all other AirPod models, which powers features like voice isolation and nod/shake-your-head Siri interactions or lossless audio support. That’s a slightly sour note, but on the whole, the AirPods lineup looks (and sounds) better than ever.

But, still, flying home from California on Tuesday, I was left with a feeling best described as ennui. On Threads, I summarized my feelings with one short sentence:

The obvious truth is that we all, including Apple, miss Steve Jobs.

Quoting me, Walt Mossberg responded:

This👇. Absolutely true. The post-Steve Jobs Apple has been a phenomenal money-making machine and has had a few notable product successes like AirPods and the Apple Watch. But it hasn’t replicated the big game changer product experience of the Jobs era.

I’ve been pondering this for the remainder of the week. One factor is that the iPhone defined the apex of personal computing. In the early years of PCs, everyone knew we wanted portability. Most of us — including me — thought we reached that with laptops. But laptops don’t go with us everywhere, and, it turns out, we want computers that go with us everywhere. That’s the iPhone, and the original iPhone in 2007 established the all-touch-screen form factor and general concept right out of the gate. That first iPhone blew our minds the moment Steve Jobs showed it to us.

Eventually, some company will introduce such a product again. It might be Apple. If it happens any time soon or soon-ish, it probably will be Apple. Apple, as a company, has a long-term strategy that it hopes will make it as likely as possible that it will be Apple. But there’s been no such product since the iPhone and, in my opinion, there is no technology extant today that would enable such a product. I feel confident that if Steve Jobs were alive and still leading Apple product development, there would have been no iPhone-like mind-blown-the-moment-you-first-saw-it new product in the intervening years.

Mossberg correctly cites AirPods and Apple Watches as big successes of the post-Jobs era. Not coincidentally, they are two of the three platforms Apple featured in last week’s event — and two of the three that people carry wherever they go. But we don’t really carry AirPods and Apple Watch — we wear them. They’re not more important than our iPhones, but they are more intimate, more personal.

But they’re also more subtle. When AirPods debuted many people thought they looked weird to wear. When Apple Watch debuted people were underwhelmed. But it turns out, perhaps even more so than with the iPhone, Apple nailed the design with both products right out of the gate. Apple Watch has an iconic, instantly recognizable form factor, but from a distance of more than a few feet away, it’d be hard to tell a brand-new Series 10 from 2015’s original “Series 0” models. The original watch straps remain compatible with the newest models — including even the Ultras. With AirPods, the stems have gotten noticeably shorter, but on the whole, they’re the exact same basic concept as the original models from 2016. They’re even offered in the exact same array of colors: white, white, or white.

What we’re seeing is Tim Cook’s Apple. Cook is a strong, sage leader, and the proof is that the entire company is now ever more in his image. That’s inevitable. It’s also not at all to say Apple is worse off. In some ways it is, but in others, Apple is far better. I can’t prove any of this, of course, but my gut says that a Steve-Jobs–led Apple today would be noticeably less financially successful and industry-dominating than the actual Tim-Cook–led Apple has been.

I think Apple Watch, under Jobs, would have been more like iPod was or AirPods have been: a product entirely defined by Apple, not a platform for third-party developers. (Jobs was famously reluctant to even make iPhone a platform.)

But the biggest difference is that Apple, under Jobs, was quirky, and I think would have remained noticeably more quirky than it has been under Cook. You’d be wrong, I say, to argue that Cook has drained the fun out of Apple. But I do think he’s eliminated quirkiness. Cook’s Apple takes too few risks. Jobs’s Apple took too many risks.

Tim Cook is no mere bean counter. Far from it. He shares with Jobs a driving ambition to change the world. Cook, just like Jobs, surely relates deeply to this quip from Walt Disney: “We don’t make movies to make money. We make money to make more movies.” But the ways Cook is driven to change the world are different.

Jobs often wore his heart on his shirtsleeve, not merely in public but on stage. Remember the 2010 WWDC keynote, when Jobs had an iPhone demo fail because the Wi-Fi wasn’t working, and 20 minutes later he came back on stage and angrily demanded that the media turn off their portable Wi-Fi base stations being used for live-blogging the keynote? He was fucking angry and he let us know it. You simply didn’t mess with a Steve Jobs keynote.

Cook almost never reveals his true passionate self in public. But at least one time he did. At the 2014 annual shareholders meeting, Cook faced a question from a representative of the right-wing National Center for Public Policy Research (NCPPR). As reported by Bryan Chaffin at The Mac Observer:

During the question and answer session, however, the NCPPR representative asked Mr. Cook two questions, both of which were in line with the principles espoused in the group’s proposal. The first question challenged an assertion from Mr. Cook that Apple’s sustainability programs and goals — Apple plans on having 100 percent of its power come from green sources — are good for the bottom line.

The representative asked Mr. Cook if that was the case only because of government subsidies on green energy. Mr. Cook didn’t directly answer that question, but instead focused on the second question: the NCPPR representative asked Mr. Cook to commit right then and there to doing only those things that were profitable.

What ensued was the only time I can recall seeing Tim Cook angry, and he categorically rejected the worldview behind the NCPPR’s advocacy. He said that there are many things Apple does because they are right and just, and that a return on investment (ROI) was not the primary consideration on such issues.

“When we work on making our devices accessible by the blind,” he said, “I don’t consider the bloody ROI.” He said the same thing about environmental issues, worker safety, and other areas where Apple is a leader.

As evidenced by the use of “bloody” in his response — the closest thing to public profanity I’ve ever seen from Mr. Cook — it was clear that he was quite angry. His body language changed, his face contracted, and he spoke in rapid fire sentences compared to the usual metered and controlled way he speaks.

He didn’t stop there, however, as he looked directly at the NCPPR representative and said, “If you want me to do things only for ROI reasons, you should get out of this stock.”

A philosophy of “Whatever is best for the ROI” is McKinsey-flavored cowardice, not leadership. Sometimes a leader needs to make decisions with uncertain business sense, or even knowing that the decision doesn’t make business sense, but simply because their intuition or conscience tell them it’s the right thing to do. Insofar as he’s willing to make such decisions, Cook is like Jobs. But what sort of decisions those are, are very different.

Jobs was driven to improve the way computers work. Cook is driven to improve the way humans live. Accessibility and the environment are much higher priorities under Cook than they were under Jobs. Apple’s entire foray into Health has occurred under Cook’s leadership — and Health-related features were tentpole features in last week’s keynote. I wouldn’t be surprised if it cost far more money to get AirPods Pro certified as medical-grade hearing aids than Apple will make back in profits from an increase in sales. The Apple 2030 initiative to bring the company’s entire carbon footprint to net zero emissions is fundamentally about doing the right thing, not just selling more products.

Jobs emphasized making more interesting products, and maximizing surprise and delight upon their unveilings. Tim Cook wouldn’t have sent the police after Gizmodo’s purloined iPhone 4 prototype; Steve Jobs probably thought Apple took it easy on them.

Cook values predictability. But predictability is in conflict with quirkiness. You don’t need to even recognize Mark Gurman’s name to have predicted that last week’s event would focus on new iPhones, new AirPods, and new Apple Watches. Nor do you need to follow the rumor mill to have correctly guessed that all of those new products would look very similar to the models that preceded them. Evolve, evolve, evolve. There’s no resting on laurels inside Apple with any of those products. The iPhones 16, Apple Watch Series 10, and AirPods 4 are all the result of intensely-focused industry-leading engineering (including in fields like material engineering) and design. But they also all basically look exactly like all of us expected them to look.

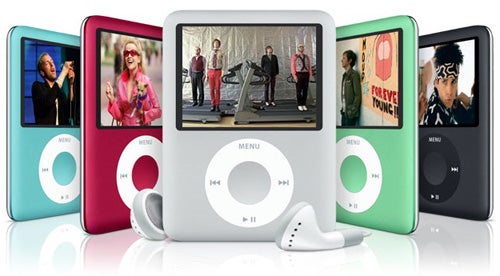

Remember the 3rd-gen iPod Nano in 2007? A.k.a. “the fat Nano”:

It’s quite possible you don’t remember the fat Nano, because it wasn’t insanely great, even though it replaced 2nd-gen iPod Nano models that were. And so a year later, with the 4th-gen Nanos, Apple went back to the tall-and-skinny design, as though the fat Nano had never happened.

That fat Nano was quirky. It was also, in hindsight, obviously a mistake. I’m quite sure that inside Apple there were designers and product people who thought it was a mistake before it shipped. Steve Jobs shipped it anyway, surely because his gut told him it was the right thing to try. Tim Cook’s Apple doesn’t make mistakes like that. That’s ultimately why Cook’s Apple is more successful — with more customers, more revenue, higher margins (and thus more profit), and more, well, sheer dominance (and, thus, more regulatory scrutiny). But it’s also why Cook’s Apple delivers fewer surprises. The delight is still there, but there’s less amazement. It’s by design. They’re not trying but failing to reach the heights of the Jobs era’s ecstatic design novelty, because those peaks had accompanying valleys. Apple today is aiming for, and achieving, utterly consistent excellence. Quirkiness no longer fits.

The lampshade iMac G4. The G4 Cube. Peripherals like the iSight camera — a product that was never intended to sell in massive numbers, but belongs in a museum alongside the best designs from Dieter Rams’s Braun. Flower Power and Dalmatian iMacs. Under Jobs, Apple made many products that were memorable at each, or at least every other, revised generation. But sometimes — like the fat Nano — they were memorable for being duds. Under Cook, Apple produces instantly iconic designs that tend only to evolve — in mostly predictable ways, on mostly predictable schedules.4

Tim Cook’s Apple has not missed any fundamental new technology or shift that would have resulted in industry-changing new products or platforms that, if he’d lived, Steve Jobs would have led Apple to create through his singular genius or sheer force of will. But I also don’t think we’d have been left with new iPhones 16 that look like last year’s iPhones 15, which looked like the iPhones 14, which looked like the iPhones 13, which looked like the iPhones 12, which looked like the iPhones 11 except that year the side rails went from rounded back to flat, like the iPhone 4 and 5 models. I can show you an iPhone 4 and you’ll know, instantly, that it is either an iPhone 4 or 4S. I can show you an iPhone 5 and you’ll know it’s either an iPhone 5 or 5S (or the first iPhone SE). If it were a black-and-slate iPhone 5 you might even know it’s a 5 specifically, not a 5S, because the anodization of the black iPhone 5 wore off over time, producing a weathered look — a patina — that I found endearing in an evocative way no subsequent iPhone has. It was an imperfection, but sometimes imperfections are what we love most about products.5 Show me an iPhone from 2020–2024 a decade from now and I’ll have to remember exactly when the Action button and Camera Control appeared to know which was which.

Cook has patience where Jobs would grow restless. In the Jobs era, when a keynote ended, we’d sometimes turn to each other and say, “Can you believe ____?” No one asked that after last week’s keynote. Much of what Apple announced was impressive. Very little was disappointing. Nothing was hard to believe or surprising.

This isn’t bad for Apple, or a sign of institutional decline. If anything, under Cook, Apple more consistently achieves near-perfection. Tolerances are tighter. Ship dates seldom slip. But it’s a change that makes the company less fun to keenly observe and obsess over. Cook’s Apple is not overly cautious, but it’s never reckless. Jobs’s Apple was occasionally reckless, for better and worse.

My dissatisfaction flying home from last week’s event is, ultimately, selfish. I miss having my mind blown. I miss being utterly surprised. I miss occasionally being disappointed by a product design that stretched quirky all the way to wacky. I miss being amazed by something entirely unexpected out of left field. Poor me, stuck only with the announcement of noticeably improved versions of three products — three product families — that zillions of people around the world, myself included, carry with us wherever we go.

-

Moleskine has long made thin, vaguely Field-Notes-y “Cahier” notebooks, but they suck. After just a few days in my back pocket, pages would start falling out. Field Notes aren’t just fun; they are meant to be used and abused. ↩︎︎

-

Also known as the iPod Nano pocket. ↩︎︎

-

The overall devices are now, once again, slightly larger with the 16 Pro and Pro Max, too — which is not a positive for fans of smaller iPhones. iPhone 12/13 Mini holdouts, this footnote is for you. ↩︎︎

-

I also believe that Apple would have gone back to live-on-stage keynotes, post-Covid, if Jobs were still around. The differences between those two keynote formats — live stage events vs. pre-filmed movies — are a good proxy for the changes to Apple as a whole. Apple’s modern pre-filmed keynotes are better for the company and better for most people who want to watch them. (Viewership numbers, I am reliably told, are higher than ever — and today dwarf the viewership of Jobs-era keynotes.) They’re far more interesting visually and more information-dense. (No need to wait for new presenters to walk on stage and then off again. Just cut to a new scene.) They’re more expensive to produce but the results are 100 percent predictable. No Apple keynote demo will ever fail again. But they’re also less exciting. Demo fails are fun (from the audience, not from the stage) and — as noted above, w/r/t the Wi-Fi at WWDC 2010 — memorable. And the possibility that any live demo might fail adds a degree of palpable tension to every demo, even the ones that wind up going off without a hitch. It’s like the difference between watching a live motorcycle stunt show and a Fast and Furious movie. The movie looks better, but carries no sense of actual danger. ↩︎︎

-

Or people. ↩︎︎

| Previous: | The iOS Continental Drift Fun Gap |

| Next: | The iPhones 16 |