By John Gruber

WorkOS: APIs to ship SSO, SCIM, FGA, and User Management in minutes. Check out their launch week.

Open and Shut

Friday, 1 March 2013

Tim Wu, writing for The New Yorker “News Desk”, has done us all a grand favor by penning a sort of grand unified theory on how the “open beats closed” axiom can be true in the face of Apple’s decade-long success: “Does a Company Like Apple Need a Genius Like Steve Jobs?” Wu’s conclusion: yes, Apple is falling back to earth sans Jobs, and the normalcy of open beating closed will return any moment now. Let’s consider his argument.

Right from the start:

The old tech adage is that “open beats closed.” In other words, open technological systems, or those that allow interoperability, always beat their closed competitors. This is an article of faith for certain engineers. It’s also the lesson from Windows’ defeat of the Apple Macintosh in the nineteen-nineties, Google’s triumph in the early aughts, and, more broadly, the success of the Internet over its closed rivals (remember AOL?). But is it still true?

Allow me to start by putting forth an alternative rule of thumb for commercial success in any market: better and earlier tend to beat worse and later. That is to say, successful products and services tend to be those that are superior qualitatively and which hit the market sooner. (Consider Microsoft’s travails in the smartphone market: the old Windows Mobile (née Windows CE) hit the market years before the iPhone and Android, but it sucked. Windows Phone is by all accounts a technically solid, well-designed system, but by the time it arrived the iPhone and Android were entrenched market leaders — it was too late.) You don’t have to be best or first, but the winners are likely to be those which fare well in both regards.

There is nothing profound or insightful (or original) about this theory; it is simply common sense. My point though, is that open-vs.-closed has very little to do with commercial success, in and of itself. Openness carries no magic.

Consider Wu’s purported canonical examples:

“Windows’ defeat of the Apple Macintosh in the nineteen-nineties” — The Wintel duopoly certainly ate the Mac’s lunch in the ’90s, but this coincided with the nadir of the Mac’s qualitative superiority. PCs were beige boxes; Macintoshes were slightly better-looking beige boxes. Windows 95 was vastly improved over Windows 3; the classic Mac OS had barely evolved in a decade, whilst Apple squandered its efforts on pie-in-the-sky next-generation systems that never saw the light of day — Taligent, Pink, Copland. Windows 95 even took to borrowing visual cues not from the Mac but from the best-looking OS of the day, NeXTStep.

Apple’s and the Mac’s problems in the ’90s had nothing to do with Apple being more closed and everything to do with the quality of the products. And, as we now know, this “defeat” was only temporary. Apple, counting only Macintosh and no iOS devices, is the single-most profitable PC maker in the world, and in the top five in terms of unit sales. For the last six years, Mac sales have outgrown the PC industry as a whole every single quarter. The Mac’s resurgence had nothing to do with being more open, and everything to do with improved quality: a modern operating system, well-designed software, and hardware designs that the entire rest of the industry now copies slavishly and shamelessly.

The Mac was closed in the ’80s and thrived, much like Apple does today: with a decent but minority market share, and very healthy profit margins. It began to suffer — both in terms of scarily dwindling market share and unprofitability — only in the mid-’90s. At this point, the Mac had become no more closed, but had become technically and aesthetically stagnant. And then came Windows 95, which altered the closed/open equation not one bit, but which closed the design quality gap with the Mac significantly. Windows thrived, the Mac withered, and it had nothing to do with openness and everything to do with engineering and design quality. Windows had gotten a lot better, and the Mac had not.

Even more telling, and more damning to Wu’s use of this as a case study, is that soon after Windows 95, Apple radically opened up the Mac OS, in a use of the word “open” that Wu expressly states is what he means by the term: they licensed the OS to other PC makers to produce Mac clones. This was the most open decision — in Wu’s sense of the word open — in the entire history of Apple Computer Inc.

And it nearly bankrupted the company.

Mac OS’s share of the overall PC market remained stagnant, but Apple’s share of Mac hardware sales, particularly lucrative high-end models, plummeted.

When Jobs and his team from NeXT took control of Apple, they shredded the licensing program, returned the company to its integrated control-the-whole-experience roots, and got to work on one thing: designing better — but absolutely closed — hardware and software. It worked.

“Google’s triumph in the early aughts” — By this Wu surely means Google web search. What exactly is or ever was more “open” about Google’s web search than any of its competitors, then or now? Everything about it is closed: the source code, the ranking algorithms, even the setup and locations of Google’s vaunted data centers are famously kept secret. Google came to dominate search for one reason: it offered a vastly superior product. It was faster, far more accurate and clever, and visually far less cluttered.

“The success of the Internet over its closed rivals (remember AOL?)” — Here Wu almost makes sense. The Internet truly is a triumph of openness, perhaps the triumph of openness. But AOL wasn’t really competing against “the Internet”. AOL is a service. The Internet is a worldwide communal system. You still need a service to connect to the Internet. AOL lost not to the Internet but to cable and DSL providers. And AOL was crap — badly-written, horribly-designed software that connected you to the Internet via appallingly slow and finicky dial-up modems.

The adage has been seriously questioned over the last few years, primarily because of one firm. Apple, ignoring the ideals of engineers and the preaching of tech pundits, steadfastly stuck to a semi-closed strategy — or an “integrated” one, as it likes to say — and defied the rule.

The “rule” has been seriously questioned all along by some of us, because it’s horseshit; not that the opposite is true (that closed tends to beat open), but rather, that open-vs.-closed carries no special weight in determining success as a general rule. Apple is not an exception to the rule; rather, it is a perfect example that the rule is nonsense.

But now, over the last six months, in ways little and large, Apple has begun to stumble. Accuse me of overreading, but I propose a revision of the old adage: closed can beat open, but you have to be genius. Under normal conditions, in an unpredictable industry, and given regular levels of human error, open still beats closed. Stated a different way, a firm gets to be closed in exact proportion to its vision and design talent.

Would not a simpler theory be that companies with visionary leaders and talented designers (or employees in general) tend to succeed? What Wu is arguing here is that “closed” companies are somehow more in need of vision and talent than “open” ones, which is folly. (Open standards certainly succeed more easily than closed ones, but that’s not what Wu is arguing here. He’s talking about companies and their success.)

To explain, I need to first be careful about what I mean by “open” and “closed,” words that are widely used in the tech industry, but with various meanings. The truth is that no company is completely open or completely closed; they exist on a spectrum, somewhat like the one that Alfred Kinsey used to describe human sexuality. Here, I mean it as the combination of three things.

First, “open” and “closed” can refer to how permissive a tech firm is, with respect to who can partner with or interconnect with its products to reach consumers. We say an operating system like Linux is “open” because anyone can design a device that runs Linux. In contrast, Apple is very selective: it would never license iOS to run on a Samsung phone, or sell the Kindle in an Apple store.

No, they likely wouldn’t sell Kindle hardware in an Apple Store, any more than they would sell Samsung phones or Dell computers. Nor do Dell or Samsung sell Apple products. But Apple does have the Kindle app in the App Store.

Second, openness can describe how impartially a tech company treats other firms in comparison to how it treats itself. Firefox, the browser, treats most Web sites about the same. Apple, in contrast, always treats itself better. (Try removing iTunes from your iPhone.)

That’s the entirety of Wu’s second meaning of “open” — a comparison between a web browser and an operating system. But Apple has its own web browser, Safari, which, just like Firefox, treats all websites the same. And Mozilla now has its own mobile OS, on which, I’ll bet, there are at least some apps you cannot remove.

Third, and finally, it describes how open, or transparent, the company is about how its products work, and how to work with them. Open-source products, or those that rely on open standards, make their source code available widely. Meanwhile, a firm like Google might be open in many respects, but it guards things like its search-engine code very carefully. In tech, the standard metaphor to describe this last difference is that of a cathedral versus a bazaar.

Wu even admits that Google’s crown jewels — its search engine and the amazing data centers that power it — are every bit as closed as much of Apple’s software and makes no mention of Apple’s leadership on open source projects like WebKit and LLVM.

Even Apple needs to be open enough not to annoy consumers too much. You can’t run Adobe’s Flash on an iPad, but you can plug nearly any kind of earphones into it.

Flash? What year is it? You can’t run Flash on Amazon’s Kindle tablets, or Google’s Nexus tablets and phone either.

The idea that “open beats closed” is a new one. For most of the twentieth century, integration was widely believed to be the superior form of business organization. […]

The conventional wisdom began to change in the nineteen-seventies. In technology markets, from the eighties through the mid-aughts, open systems repeatedly defeated their closed competitors. Microsoft Windows defeated its rivals by being more open: unlike Apple’s operating system, which was technically superior, Windows ran on any hardware, and ran nearly any software.

Again, the Mac was not defeated, and, looking at the decades-long history of the PC industry, the evidence suggests that openness has little to do with success, and with the Mac in particular, if anything it proves the opposite. The Mac’s roller-coaster trajectory — up in the ’80s, down in the ’90s, up in the ’00s and continuing through today — corresponds exactly to the competitive quality of Apple’s hardware and software, and not at all to its openness. The Mac has succeeded most when closed, least when open.

At the same time, Microsoft also defeated a vertically integrated I.B.M. (Remember Warp O.S.?)

I do, but apparently Wu does not, because it was called “OS/2 Warp”.

If openness is the key to Windows’s success, whither Linux on the desktop? Linux is truly open by anyone’s definition of the word, far more open than Windows could ever be. And it has been a nearly complete dud as a desktop operating system, where it has never been all that good, qualitatively.

On the server though, where Linux has long been widely regarded as technically excellent — fast and reliable — it has been a tremendous success. If openness were key, Linux should have succeeded everywhere. It has not. It has only succeeded where it is actually good, as a system for servers.

Google was boldly open in its original design, and sailed past the selective pay-for-placement design of Yahoo.

Describing Google’s evisceration of the first generation of search engines as having anything at all to do with “openness” is absurd. Google search was better — not just a little better, but way better, like 10 times better — in every single regard: accuracy, speed, clarity, and even visual design.

Not one person, ever, tried Google search for the first time after years of using Yahoo, Altavista, and the like and said to themselves, “Wow, this is way more open!”

Most of the winner firms in the eighties to the aughts, like Microsoft, Dell, Palm, Google, and Netscape, were open. And the Internet itself, a government-funded project, was both incredibly open and incredibly successful. A movement was born, and with it the rule that “open beats closed.”

Microsoft: Not really open, they just license their OSes — not for free but for, you know, money — to any company that will pay.

Dell: Open how? Dell’s peak success had nothing to do with openness and everything to do with having figured out ways to produce commodity PCs cheaper and quicker than its competitors. When cheap fast production itself became a commodity, with the rise of outsourced Chinese manufacturing and assembly, Dell’s advantage disappeared, along with its relevance. And, not exactly a shining example of sustained success.

Palm: More open than Apple how? And, uh, out of business.

Netscape: They built browsers and servers for the truly open web, but their software was closed. And what cost them their lead in the browser market was a two-fold attack by Microsoft: (1) Microsoft made a better browser, and (2) in a completely closed (and eventually deemed-to-be-illegal) fashion, they used their control over the closed Windows operating system to bundle and favor IE over Netscape Navigator.

The triumph of open systems revealed a major defect in closed designs.

Rather, Wu’s examples have revealed a major defect in his entire thesis: it is not true.

Which brings us to the aughts, and Apple’s great run. For about twelve years, Apple successfully beat the rule. But that’s because it had the best of all possible systems; namely, a dictator with absolute control who was also a genius. Steve Jobs was the corporate version of Plato’s ideal: the philosopher-king more effective than any democracy. The firm was dependent on one centralized mind, but he made very few mistakes. In a world without errors, closed beats open. Consequently, for a while, Apple bested its rivals.

Wu’s approach to this entire subject is backwards. Rather than evaluate the facts and draw a conclusion regarding the importance of openness to commercial success, he instead started with a belief in the axiom and attempted to massage the facts to fit the dogma. Thus, Wu argues, Apple’s success over the past 15 years is not incontrovertible proof that the “open beats closed” axiom is false, but rather was the result of Steve Jobs having possessed singular abilities that trumped the power of openness. He, and he alone, could walk on water.

Wu mentioned the word “iPod” not a single time in his essay, and “iTunes” only once — in the section quoted above about not being able to delete the iTunes app from an iPhone. Those are convenient omissions from a piece arguing that “open beats closed”. These are both canonical examples suggesting that other factors are more important to success — that better beats worse, integrated beats fragmented, simple beats complicated.1

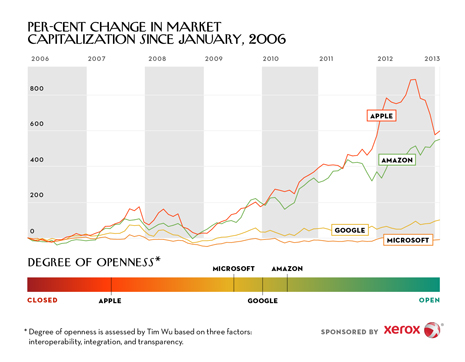

There’s an “infographic” that accompanies Wu’s article, and it is mind-bogglingly vapid. It must be seen to be believed.

Market cap over time, so far so good. But the colors? Nick Traverse explains:

The infographic here shows the market capitalization of four big technology companies since 2006 — Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft. Wu developed a metric for assessing the “openness” of companies, scored on three factors: interoperability, integration, and transparency. With 1 being closed, and 10 being open, here’s how they rank:

Apple: 2.0

Microsoft: 5.0

Google: 5.7

Amazon: 6.3

That’s the extent of the work shown to justify these scores. Not only did Wu choose these attributes of “openness” arbitrarily and simply make up values for the interoperability / integration / transparency scores for each company, he doesn’t even reveal what these individual per-attribute scores are. All we get are these ostensibly quantitative overall scores: 2.0, 5.0, 5.7, 6.3. If pseudoscience gobbledygook were toxic, we’d all be dead having gazed upon this chart.

Traverse continues:

Wu’s theory is that open should generally do better than closed, unless the closed company is run by a genius. And though this is just a smattering of data, the chart seems to bear the theory out. The stock prices of Microsoft, Google, and Amazon more or less correlate to their openness scores. Apple, the most closed of the four, does the best — until about a year after Steve Jobs dies. Since then, it has plummeted.

The stock values over time are data; the openness scores are nonsense, a metric Tim Wu pulled out of his ass. But even if we accept everything in this chart as Wu and The New Yorker intend — that Wu’s openness scores are meaningful and accurate, and that stock price is a reliable measure of a company’s success — this graphic does not show any sort of correlation between openness and success, nor, even, that Apple is suffering without Steve Jobs.

Traverse is correct that Apple’s stock price has dropped by about 30 percent in recent months, beginning about a year after Jobs’s death. But he neglects to mention that in the year after his death, the stock price rose so high that, despite the recent drop, it remains up, significantly, from the date of Jobs’s death.

According to Wu, Apple’s stock should continue to slide; only time will tell if he’s right. But what of the other four companies he chose? Microsoft’s score of 5.0 is the lowest of the three and indeed its stock performance since 2006 (the beginning of the graphic) is the worst — pretty much completely flat. But Google’s 5.7 is halfway between Amazon’s 6.3 and Microsoft’s 5.0, but their stock price has fared only slightly better than Microsoft. None of these companies’ stock prices show any correlation to the openness scores Wu assigned them, with the exception of Amazon. But how in the world did Amazon get a higher “openness” score than Google? Google released Android as an actual open source project; Amazon took Android and created their own closed source branch for the Kindle Fire. The Kindle e-readers are every bit as closed as the iPod. Transparency? Apple releases sales numbers for all of its product categories, each and every quarter. Apple releases numbers regarding how many apps have been downloaded from the App Store, how much money it has paid to developers, how many songs they’ve sold through iTunes, and how many books have been downloaded through iBooks. Amazon never releases sales numbers for anything — not for the Kindle, not for apps, nothing. Just bromides about having sold “the most ever”, or such and such percent more than an earlier quarter. It’s hard to think of a reason why Amazon would score as more open than Google other than that their stock has done better in recent years and that Wu assigned the scores to fit the narrative.

Not to mention that if Wu had chosen profitability rather than stock price as the metric for corporate success, the chart would show a reverse correlation between openness and success: Apple first, Microsoft second, Google third, and Amazon a distant fourth at nearly zero. (I’m not proposing that this would be any less nonsensical than Wu’s use of stock prices. For one thing, Amazon seemingly turns little-to-no profit on purpose. But it’s no less valid than Wu’s use of stock price, especially when comparing the three companies in the group that are pursuing profitability.)

The dogmatic assumption that openness correlates to success, evidence to the contrary be damned, overcomplicates the argument. “Wu’s theory is that open should generally do better than closed, unless the closed company is run by a genius.” Take the open/closed stuff out of that premise, and you’re left with something like this: Companies run by geniuses should generally do better than those which are not. That sounds about right.

Wu concludes his essay with this advice:

In the end, the better your vision and design skills, the more closed you can try to be. If you think your product designers can duplicate the nearly error-free performance of Jobs over the past twelve years, go for it. But if mere mortals run your firm, or if you’re facing an extremely unpredictable future, the economics of error suggest an open system is safer. Maybe rely on this test: wake up, look in the mirror, and ask yourself, Am I Steve Jobs?

The key word here is “safer”. Don’t try to do it all. Don’t do something different. Don’t rock the boat. Don’t question conventional wisdom. Go with the flow.

That’s what bothers people about Apple. Everyone used Windows, why couldn’t Apple just settle for making stylish Windows machines? Smartphones required hardware keyboards and removable batteries; why did Apple make theirs with neither? Everyone knew you needed Flash Player for the “full web experience”, why did Apple drop it? 16 years after the ad campaign, “Think Different” has proven itself to be more than glib marketing. It is a simple, serious motto that serves as a guiding light for the company.

I think what Wu and his brethren believe is not that companies win by being “open”, but that they win by offering choices.

Who is Apple to decide which apps are in the App Store? That no phone will have a hardware keyboard or removable battery? That modern devices are better off without Flash Player and Java?

Where others offer choices, Apple makes decisions. What some of us appreciate is what so rankles the others — that those decisions have so often and consistently been right.

-

No mention, either, of Apple’s leadership on eliminating DRM from music in the iTunes Store — a stance surely more open than closed. ↩︎