By John Gruber

WorkOS: APIs to ship SSO, SCIM, FGA, and User Management in minutes. New: Summer Launch Week.

- Apple Sues Jon Prosser Over iOS 26 Leaks ★

-

Eric Slivka, reporting last night for MacRumors:

While the Camera app redesign didn’t exactly match what Apple unveiled for iOS 26, the general idea was correct and much of what else Prosser showed was pretty close to spot on, and Apple clearly took notice as the company filed a lawsuit today (Scribd link) against Prosser and Michael Ramacciotti for misappropriation of trade secrets.

Apple’s complaint outlines what it claims is the series of events that led to the leaks, which centered around a development iPhone in the possession of Ramacciotti’s friend and Apple employee Ethan Lipnik. According to Apple, Prosser and Ramacciotti plotted to access Lipnik’s phone, acquiring his passcode and then using location-tracking to determine when he “would be gone for an extended period.” Prosser reportedly offered financial compensation to Ramacciotti in return for assisting with accessing the development iPhone.

Lipnik, the Apple employee, was fired, but isn’t named in the lawsuit because seemingly all he did was improperly secure his device running an early build of iOS 26. That’s against company policy, but not against the law.

Prosser, on X, disputes the description of his involvement in Apple’s lawsuit:

For the record: This is not how the situation played out on my end. Luckily have receipts for that.

I did not “plot” to access anyone’s phone. I did not have any passwords. I was unaware of how the information was obtained.

Looking forward to speaking with Apple on this.

Prosser also shared one screenshot of his Signal message correspondence with Ramacciotti.

(MacRumors’s copy of Apple’s lawsuit is hosted at Scribd, which is free to read in a browser, but requires a paid account to download the original PDF. I’m hosting a copy of the PDF here.)

Thursday, 17 July 2025

- Network Pinheads at CBS Are Ending ‘The Late Show’ ★

-

The above links to an Instagram reel with Colbert breaking the news at the start of his show airing tonight. Here’s the same clip on X, if you prefer. He, apparently, was as surprised as anyone.

Here’s Jed Rosenzweig’s story at (the excellent) LateNighter:

“The Late Show with Stephen Colbert will end its historic run in May 2026 at the end of the broadcast season,” the network said in a statement. “We consider Stephen Colbert irreplaceable and will retire The Late Show franchise at that time. We are proud that Stephen called CBS home. He and the broadcast will be remembered in the pantheon of greats that graced late night television.”

The statement was issued jointly by George Cheeks (Co-CEO of Paramount Global and President and CEO of CBS), Amy Reisenbach (President of CBS Entertainment), and David Stapf (President of CBS Studios).

CBS emphasized that the decision was not related to performance or content: “This is purely a financial decision against a challenging backdrop in late night. It is not related in any way to the show’s performance, content or other matters happening at Paramount.”

This stinks to high hell. Colbert has the best ratings in late night TV.

Wednesday, 16 July 2025

- Rare Earth Magnet Maker MP Materials Is Having a Big Week ★

-

Spencer Kimball, reporting for CNBC one week ago:

The Defense Department will become the largest shareholder in rare earth miner MP Materials after agreeing to buy $400 million of its preferred stock, the company said Thursday.

MP Materials owns the only operational rare earth mine in the U.S. at Mountain Pass, California, about 60 miles outside Las Vegas. Proceeds from the Pentagon investment will be used to expand MP’s rare earths processing capacity and magnet production, the company said. Shares of MP Materials soared about 50% to close at $45.23. Its market capitalization grew to $7.4 billion, an increase of about $2.5 billion from the previous trading session. [...]

MP Materials CEO James Litinsky described the Pentagon investment as a public-private partnership that will speed the buildout of an end-to-end rare earth magnet supply chain in the U.S.

“I want to be very clear, this is not a nationalization,” Litinsky told CNBC’s “Squawk on the Street” on Thursday. “We remain a thriving public company. We now have a great new partner in our economically largest shareholder, DoD, but we still control our company. We control our destiny. We’re shareholder driven.” U.S. miners are facing a unique threat from “Chinese mercantilism,” Litinsky said. The Pentagon investment in MP could serve as a model for similar deals with other U.S. companies, the CEO said.

This news caught my eye when Taegan Goddard linked to it from Political Wire yesterday (quipping, “I’m old enough to remember when this was called ‘socialism’”), because yesterday MP Materials landed a $500 million deal from Apple. Apple Newsroom:

Today Apple announced a new commitment of $500 million with MP Materials, the only fully integrated rare earth producer in the United States. With this multiyear deal, Apple is committed to buying American-made rare earth magnets developed at MP Materials’ flagship Independence facility in Fort Worth, Texas. The two companies will also work together to establish a cutting-edge rare earth recycling line in Mountain Pass, California, and develop novel magnet materials and innovative processing technologies to enhance magnet performance. The commitment is part of Apple’s pledge to spend more than $500 billion in the U.S. over the next four years, and builds on the company’s long history of investment in American innovation, advanced manufacturing, and next-generation recycling technologies. [...]

When complete, the new recycling facility in Mountain Pass, California will enable MP Materials to take in recycled rare earth feedstock — including material from used electronics and post-industrial scrap — and reprocess it for use in Apple products. For nearly five years, Apple and MP Materials have been piloting advanced recycling technology that enables recycled rare earth magnets to be processed into material that meets Apple’s exacting standards for performance and design. The companies will continue to innovate together to improve magnet production, as well as end-of-life recovery.

Apple pioneered the use of recycled rare earth elements in consumer electronics, first introducing them in the Taptic Engine of iPhone 11 in 2019. Today, nearly all magnets across Apple devices are made with 100 percent recycled rare earth elements.

The timing of these two announcements could be purely coincidental, but I can’t help but wonder if both moves were fueled by concerns about China cornering the market on rare earth magnets. Conversely, I wonder if this deal (and promotion of it) from Apple is aimed just to placate the Trump administration. A $500 million commitment is surely a big deal for MP Materials. It’s not that big a deal for Apple. What makes it interesting is that it’s with an American company.

- More on Commodore, Apple, and the Inchoate Personal Computer Era ★

-

Jason Snell:

If you find yourself walking down the street in the 1980s and you see someone coming who prefers the VIC-20 to the Apple II, cross to the other side of the street. (That said, the VIC-20 really was revolutionary. It was by far the most affordable home computer anyone had ever seen at that point. It was laughably underpowered … but: it was only $300! They sold a million of ’em.)

Snell takes issue (correctly!) with Drew Saur’s framing of the Apple II as “corporate”. As Snell points out, Commodore was founded by a suit — Apple was founded by two guys whose first collaboration was making phone-phreaking blue boxes.

But a more pertinent point was made by Dr. Drang on Mastodon:

I don’t want to get on the bad side of @gruber and @jsnell, but when they say the Commodore 64 cost $600, that’s misleading. Yes, it cost $600 when it was released, but its price dropped quickly. By the time I bought one in late ’83 or early ’84, it was selling for $200 at Kmart. To recognize that it was a great computer for the price, you have to know what that price really was.

When I wrote the other day that the C64 cost $600, it didn’t jibe with my memory. But my thinking is too set in the ways of Apple, where a computer debuts at a price and then stays at that price. A price around $200 is more what I remember for the C64, at a time when a bare-bones IIe cost $1,400. Inflation-adjusted, $200 in 1984 is about $620 today, and $1,400 is about $4,300. That’s why so many more kids of my era got their parents to spring for a Commodore 64 but not an Apple II. They were rivals in some sense, but really, the Apple II was a different class of computer, and cost nearly an order of magnitude more. Inflation-adjusted, it’s very similar to the difference in both price and capabilities of the Meta Quest versus Vision Pro.

(Me, I didn’t own a computer until I went to college. My parents wouldn’t buy me one because they feared if they did, I’d never leave the house. I resented it at the time, but in hindsight, they might have been right. I didn’t fight too hard because we had an Atari 2600 and a generous budget for game cartridges. Plus, my grade school had a few Apple IIe’s (alongside a bunch of cheap TI-99/4A’s), and my middle/high school had an entire lab of Apple IIe’s and IIc’s.)

Tuesday, 15 July 2025

- Drew Saur’s Ode to the Commodore 64 ★

-

Drew Saur, pushing back on my post slagging on the Commodore 64:

I cannot argue with your nostalgia. It is uniquely yours.

That said: The Commodore 64 as cheap-feeling and inelegant! Oh my.

I was fourteen when the Commodore 64 came out, and I want to convey — in as brief a form as I can — why it captured so many hearts during the 8-bit era.

What a great post. Fond memories all the way down the stack with that whole era of computing. As I told Saur in email, my fondest memory of the Commodore 64 is that they sold them at Kmart, and for years had a working model on display. And every time I’d go to Kmart with my mom, I’d swing by the electronics department and type:

10 PRINT "KMART SUCKS!!!!" 20 GOTO 10 RUNSometimes I’d be clever and do something like add an incrementing number of spaces to make the lines go diagonally. Something like:

5 LET X = 0 10 PRINT SPC(X); "KMART SUCKS!" 20 X = X + 1 30 IF X > 28 THEN X = 0 35 FOR T = 0 TO 100 : NEXT : REM SLOW DOWN 40 GOTO 10 RUNThis never got old for me. Try it yourself. (And of course I never actually commented my code at Kmart — that

REMis for you, if you’re wondering what that do-nothingFORloop is for.) - The Party of ‘Free Speech’ ★

-

David A. Graham, writing at The Atlantic:

Not that long ago, believe it or not, Donald Trump ran for president as the candidate who would defend the First Amendment.

He warned that a “sinister group of Deep State bureaucrats, Silicon Valley tyrants, left-wing activists, and depraved corporate news media” was “conspiring to manipulate and silence the American people,” and promised that “by restoring free speech, we will begin to reclaim our democracy, and save our nation.” On his first day back in office, Trump signed an executive order affirming the “right of the American people to engage in constitutionally protected speech.”

If anyone believed him at the time, they should be disabused by now. One of his most brazen attacks on freedom of speech thus far came this past weekend, when the president said that he was thinking about stripping a comedian of her citizenship — for no apparent reason other than that she regularly criticizes him.

“Because of the fact that Rosie O’Donnell is not in the best interests of our Great Country, I am giving serious consideration to taking away her Citizenship. She is a Threat to Humanity, and should remain in the wonderful Country of Ireland, if they want her,” he posted on Truth Social.

The people who griped that the Biden Administration was anti-free-speech because they ... checks notes ... applied soft pressure on companies like Meta to clamp down on algorithmically promoting disinformation are pretty quiet these days.

Monday, 14 July 2025

- ‘Elon Musk Gives Himself Another Handshake’ ★

-

Nick Heer, Pixel Envy on the news that SpaceX “invested” $2 billion in the xAI money pit:

This comes just a few months after xAI acquired X, one year after Musk shifted a bunch of Tesla-bound Nvidia GPUs to xAI, and just a few years after he used staff from Tesla to work on Twitter. So, to recap: he has moved people and resources from two publicly traded companies to two privately owned ones, has used funds from one of his privately owned companies to buy another one of his privately owned companies, and is now using one of his

publicly tradedprivately owned companies to give billions of dollars to (another) one of his privately owned ones.Musk can and should be able to do whatever he wants with his privately held companies, like X Corp and SpaceX. But the way he treats Tesla Motors, which is publicly traded, as though it’s just part of his personal fiefdom is absurd. And the European Commission isn’t fooled.

- Lee Elia, Former Major League Manager, Dies at 87 ★

-

Steve Berman, The Athletic:

Lee Elia, who managed the Philadelphia Phillies and Chicago Cubs for two seasons apiece but is perhaps best known for a profane postgame rant critical of Chicago fans, died on Wednesday. He was 87. The Phillies announced his death in a statement on Thursday, though they did not say where he died or cite a cause. [...]

The team noted that Elia was a Philadelphia native who signed with the Phillies in 1958. He was in the organization on and off throughout the decades, including as a minor league player, manager, scout and director of instruction. He was the third-base coach for the Phillies team that won the 1980 World Series.

You’ll never hear a better example of how to talk like a Philadelphian than Elia’s famed 1983 rant, after the Cubs opened the season 5-14. Earmuffs for any (non-Philadelphian) children in the room.

- Elmore Leonard’s Perfect Pitch ★

-

Anthony Lane, in a crackerjack piece for The New Yorker on the writing and work of Elmore Leonard:

So, when does Leonard become himself? Is it possible to specify the moment, or the season, when he crosses the border? I would nominate “The Big Bounce,” from 1969 — which, by no coincidence, is the first novel of his to be set in the modern age. As the prose calms down, something quickens in the air, and the plainest words and deeds make easy music: “They discussed whether beer was better in bottles or cans, and then which was better, bottled or draft, and both agreed, finally, that it didn’t make a hell of a lot of difference. Long as it was cold.”

What matters here is what isn’t there. Grammatically, by rights, we ought to have an “As” or a “So” before “long.” If the beer drinkers were talking among themselves, however, or to themselves, they wouldn’t bother with such nicety, and Leonard heeds their example; he does them the honor of flavoring his registration of their chatter with that perfect hint of them. The technical term for this trick, as weary students of literature will recall, is style indirect libre, or free indirect discourse. It has a noble track record, with Jane Austen and Flaubert as front-runners, but seldom has it proved so democratically wide-ranging — not just libre but liberating, too, as Leonard tunes in to regular citizens. He gets into their heads, their palates, and their plans for the evening. Listen to a guy named Moran, in “Cat Chaser” (1982), watching Monday-night football and trying to decide “whether he should have another beer and fry a steak or go to Vesuvio’s on Federal Highway for spaghetti marinara and eat the crisp breadsticks with hard butter, Jesus, and have a bottle of red with it, the house salad ... or get the chicken cacciatore and slock the bread around in the gravy ...”

The ellipses are Leonard’s, or, rather, they are Moran’s musings, reproduced by Leonard as a kind of Morse code. We join in with the dots. But it’s the “Jesus” that does the work, yielding up a microsecond of salivation, and inviting us to slock around in the juice of the character’s brain.

The genius in the second example is the verb choice: slock. There are dozens of verbs that could have worked there, but none better.

Leonard is probably tops on the list of authors whose work I love, but of which I haven’t read nearly as much as I should. There are novelists who are good at creating (and voicing) original vivid characters, novelists who are good at plot, and novelists who are just great at writing. Leonard hits the trifecta.

- Experts Said This Was a Damn Clever Post by Jason Kottke ★

-

Jason Kottke:

Large media companies, and the NY Times in particular these days, like to use the phrase “experts said” instead of simply stating facts. The thing is, many other statements of plain truth in that brief Times post lack the confirmation of expertise. To aid the paper in steering their readers away from notions of objective truth, here’s a suggested rewrite of that Bluesky post.

- Reborn Commodore Is Taking Pre-Orders for New Commodore 64 Models ★

-

Last year, retro computing YouTuber Christian “Peri Fractic” Simpson bought the branding rights and some of the IP belonging to Commodore (which rights have been transferred five times since the original company went bankrupt in 1994). Last week they launched their first product:

This is the first real Commodore computer in over 30 years, and it’s picked up a few new tricks.

Not an emulator. Not a PC. Retrogaming heaven in three dimensions: silicon, nostalgia, and light. Powered by a FPGA recreation of the original motherboard, wrapped in glowing game-reactive LEDs (or classic beige of course).

Via Ernie Smith, who has been following this saga thoughtfully.

This is, no question, a fun and cool project, and I hope it succeeds wildly. But personally, the Commodore 64 holds almost no nostalgic value for me. The Commodore 64 — which came out in 1982, when I was 9 — always struck me as cheap-feeling and inelegant. Like using some weird computer from the Soviet Union. Just look at its keyboard. It’s got a bunch of odd keys, like “Run Stop” and “Restore”, and all sorts of drawing-related glyphs (used when programming) printed on the sides of the keycaps. Now compare that to the keyboards from the Apple II Plus (1979), which has just one weird key, “REPT” (for Repeat — you needed to press and hold REPT to get other keys to repeat, which, admittedly, seems inexplicable in hindsight), and to the Apple IIe (1983), which has no weird keys and whose keyboard looks remarkably modern lo these 42 intervening years.

That said, while both systems came with 64 kilobytes of RAM, the Apple IIe cost $1,400 when it debuted (~$4,600 today, inflation adjusted); the Commodore 64 cost $600 (~$2,000 today). Some things haven’t changed about the computer industry in my lifetime.

The most interesting computers Commodore ever made, by far, were the Amigas. The Amiga brand and IP were cleaved from Commodore long ago, and alas, the new Commodore doesn’t have them. But they’ve expressed interest in buying them. Something like this Commodore 64 Ultimate but for an Amiga — now that might get me to reach for my credit card.

Sunday, 13 July 2025

- ‘Classic Web’ on Mastodon ★

-

Classic Web is a fun account to follow on Mastodon. Curator Richard MacManus posts half a dozen or so screenshots per day of, well, classic websites from the late 1990s and 2000s. Makes me feel old and young at the same time.

- Drata ★

-

My thanks to Drata for sponsoring this last week at DF. Their message is short and sweet: Automate compliance. Streamline security. Manage risk. Drata delivers the world’s most advanced Trust Management platform.

Saturday, 12 July 2025

- Grok 4 System Prompt Shenanigans ★

-

Simon Willison:

Grok 4 Heavy is the “think much harder” version of Grok 4 that’s currently only available on their $300/month plan. Jeremy Howard relays a report from a Grok 4 Heavy user who wishes to remain anonymous: it turns out that Heavy, unlike regular Grok 4, has measures in place to prevent it from sharing its system prompt.

Most big LLMs do not share their system prompts, but xAI has made a show out of being transparent in that regard.

In related prompt transparency news, Grok’s retrospective on why Grok started spitting out antisemitic tropes last week included the text “You tell it like it is and you are not afraid to offend people who are politically correct” as part of the system prompt blamed for the problem. That text isn’t present in the history of their previous published system prompts.

Given the past week of mishaps I think xAI would be wise to reaffirm their dedication to prompt transparency and set things up so the xai-org/grok-prompts repository updates automatically when new prompts are deployed — their current manual process for that is clearly not adequate for the job!

Transparently publishing system prompt changes to GitHub was xAI’s main “trust us” argument after the “white genocide in South Africa” fiasco mid-May. Turns out they don’t publish all of them.

Friday, 11 July 2025

- Apple and Masimo Faced Off in US Appeals Court This Week ★

-

Blake Brittain, reporting for Reuters:

Apple asked a U.S. appeals court on Monday to overturn a trade tribunal’s decision which forced it to remove blood-oxygen reading technology from its Apple Watches, in order to avoid a ban on its U.S. smartwatch imports.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit heard arguments from the tech giant, medical monitoring technology company Masimo, and the U.S. International Trade Commission over the ITC’s 2023 ruling that Apple Watches violated Masimo’s patent rights in pulse oximetry technology. [...]

Apple attorney Joseph Mueller of WilmerHale told the court on Monday that the decision had wrongly “deprived millions of Apple Watch users” of Apple’s blood-oxygen feature. A lawyer for Masimo, Joseph Re of Knobbe Martens Olson & Bear, countered that Apple was trying to “rewrite the law” with its arguments.

The judges questioned whether Masimo’s development of a competing smartwatch justified the ITC’s ruling. Apple has told the appeals court that the ban was improper because a Masimo wearable device covered by the patents was “purely hypothetical” when Masimo filed its ITC complaint in 2021. [...]

Mueller told the court on Monday that the ban was unjustified because Masimo only had prototypes of a smartwatch with pulse oximetry features when it had filed its ITC complaint. Re responded that Apple was wrong to argue that a “finished product” was necessary to justify the ITC’s decision.

This whole thing started with the Apple Watch Series 9 and Ultra 2 in 2023. I’m very surprised that we’re just two months away from the Series 11 and Ultra 3 in 2025 and it still isn’t settled. And to be clear, while it’s technically an “import ban”, all Apple Watch Series 9, Series 10, and Ultra 2 have the blood oxygen sensors. Units sold in the US after December 2023 simply have the feature disabled in software.

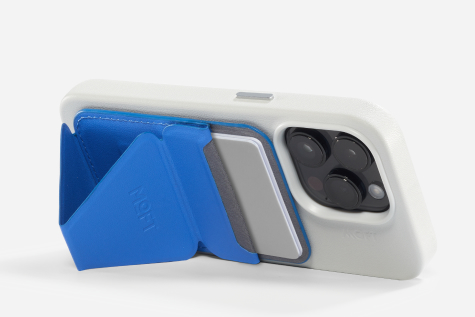

- Moft’s MagSafe-Compatible Snap-On iPhone Stand and Wallet ★

-

Here’s a product recommendation long in the making. Four years ago this month, Matthew Panzarino was my guest on The Talk Show and at one point he recommended Moft’s Snap-On iPhone Stand/Wallet. It uses a very clever origami-style folding design. Folded flat it kind of just looks like a leather MagSafe wallet. But folded open it works as a stand — and as a stand, it works both horizontally and vertically. Borrowing images from Moft’s website:

You can also use it with the stand oriented vertically but the phone horizontally.

I bought one of these right after that episode of the show, and I’ve been using it ever since. And every so often when I use it, I think to myself that I should write a post recommending it. I’ve waited so long that Panzarino has been back on The Talk Show five times since the episode in which he recommended it, but here we are. The thing is, I use it both in my kitchen and while travelling, and so I’ll often find myself in the kitchen, rooting around the drawer in which I keep it stashed, only to realize it’s downstairs in my office in my laptop bag. Or, worse, I’ll find myself looking for it in my laptop bag while I’m sitting on an airplane 35,000 feet in the air, only to realize it’s back home in my kitchen. So I ordered a second one today — which I should have done like 3.5 years ago.

I own a few similar/competing products, like these PopSocket-y rings from Anker and Belkin. I have no idea why I own both of those rings when I don’t like either of them as much as the Moft foldable stand. The problem with these rings is that they’re only able to prop the phone horizontally. Watching video is almost certainly the most common use case for these stands, but I do often use my iPhone propped up vertically, like for FaceTime calls and when I’m writing on it using a Bluetooth keyboard. I’m going to give both of these rings away — there’s nothing they do better than the Moft stand. The Moft stand even works better as a hand-holding grip.

I’ve never used the Moft stand as a wallet, but if you want to, it holds two cards. Prime “Day” lasts a week and it’s still running until midnight Pacific tonight, but the Moft stand doesn’t have a Prime Day discount: it’s the same price at Amazon as it is from Moft’s website: $30. Well worth it. I love this thing. (Buy yours wherever you want, of course, but the Amazon link a few sentences back will throw some filthy affiliate lucre my way.)

Thursday, 10 July 2025

- Linda Yaccarino Resigns as ‘CEO’ of X ★

-

Linda Yaccarino, in a post on X yesterday:

After two incredible years, I’ve decided to step down as CEO of X.

When @elonmusk and I first spoke of his vision for X, I knew it would be the opportunity of a lifetime to carry out the extraordinary mission of this company. I’m immensely grateful to him for entrusting me with the responsibility of protecting free speech, turning the company around, and transforming X into the Everything App.

I thought it couldn’t be done, but here we are today, using X for everything: news, banking, shopping, payments, messaging. It’s the only app most people use.

The Guardian, reporting on her departure:

After more than two years of Yaccarino running damage control for her boss and the platform’s myriad issues, Musk issued only a brief statement acknowledging she was stepping down.

“Thank you for your contributions,” Musk responded to Yaccarino’s post announcing her resignation. Minutes later, he began sending replies to other posts about SpaceX, artificial intelligence and how his chatbot became a Nazi.

- Yours Truly on Crossword, With Jonathan Wold and Luke Carbis ★

-

Jonathan Wold and Luke Carbis cohost a podcast called Crossword, focusing mainly on WordPress and the open web. They occasionally invite guests to join them, and it was my pleasure to join them on their latest episode:

John Gruber’s Dithering podcast with Ben Thompson was the original inspiration for Crossword’s 15-minute format. Five years later, John joins Luke and Jonathan for a wide-ranging conversation covering open versus closed platforms, the history and impact of Markdown, and a missed opportunity in WordPress. Luke goes on about the good old days, Jonathan starts thinking about a rival platform, and John makes a prediction for the ten-year follow-up episode.

While their usual format is a Dithering-esque 15 minutes, these special “perspectives” interviews run long. And unsurprisingly, mine ran long. I don’t write about the open web as much as I used to but I care about it as much as ever. I express some of my deep concerns about Substack in particular in this interview.

Wednesday, 9 July 2025

- Mark Gurman Got a Slew of Interesting Quotes Regarding Jeff Williams’s Retirement ★

-

Mark Gurman got some interesting quotes from interesting former Apple employees for his report at Bloomberg on Jeff Williams’s retirement:

“Jeff’s importance and contributions to Apple have been enormous, although perhaps not always obvious to the general public,” said Tony Blevins, a former Apple operations vice president who reported to Williams until the end of 2022. “As a shareholder, I am saddened. Time takes its toll, and it’s almost as if the band is dissolving. Jeff will be sorely missed.”

Blevins is a fascinating character. A hard-charging negotiator nicknamed “the Blevinator”, Blevins was somewhat ignominiously run out of Apple in 2022 after he appeared in a TikTok video that went viral making a joke that, out of context, seemed very crude, but was in fact just a quote from the mildly crude 1981 Dudley Moore hit movie Arthur.

“Clearly he wasn’t destined to be the Tim Cook replacement,” Bob Mansfield, the company’s former chief of hardware engineering under both Cook and co-founder Steve Jobs, said of Williams. “He’s about the same age as Tim, so that wouldn’t make much sense. The operations team at Apple is really going to miss Jeff.”

Mansfield is the only ex-Apple person I’ve seen quoted who addressed the succession issue. (And of course, no current Apple people are quoted anywhere, other than in Apple’s PR announcement of Williams’s retirement.)

Myoung Cha, who reported to Williams in the health group until 2021, said the outgoing COO’s “personal passion for health” helped shape the Apple Watch and that his presence on the team will be “hugely missed.”

“Sabih is very much cut from the Tim Cook cloth,” said Matthew Moore, a former Apple operations engineer. “Jeff was a little more product minded; Sabih is just a really brilliant operator and methodical in the same way that Tim would operate.” Moore added that Khan has already been running Apple’s operations group and that the team “won’t miss a beat.” “The concerns will be in the other areas” that Williams currently oversees, he said.

I wrote about Williams’s “overseeing” of design yesterday. Design — software at least — has already become a concern in the six years since Jony Ive left Apple, which is when design teams started reporting to Williams. And, frankly, it’s been a concern for many of us ever since Scott Forstall was fired and Ive put all design — HI and ID — under the same roof.

Apple did announce yesterday that after Williams fully retires at the end of this year, design leaders will start reporting to Tim Cook directly. Left unsaid in Apple’s announcement is who will take over Williams’s roles overseeing Apple Watch and Health. I presume Watch will simply fall under John Ternus (SVP hardware) and that Sumbul Desai, who already has the title VP of health and frequently (always?) appears during the Health segments of Apple keynotes, will report directly to Cook.

Save Yourself Some Dough on Apple Kit and Make Me Rich on Amazon Prime Day

Wednesday, 9 July 2025

It’s Amazon’s annual Prime Day sale, and if you click through this link, or any of the ones below, you can show your support for Daring Fireball by throwing the referral revenue from any purchases you make my way. You don’t pay a penny more but I get a few percentage points of your purchases. Prime Day discounts are no joke either — we need an outdoor TV for our sun-drenched deck, and I’d been putting off purchasing one out of indecision, but I pulled the trigger and saved $500 with a Prime Day discount last night. (Sometimes my procrastination pays off.)

Just about everything Amazon sells from Apple is being offered at significant discounts. Just a handful of popular ones:

- 11-inch M3 iPad Air for $480 (regularly $600).

- iPad Mini (A17 Pro) for $380 (regularly $500).

- AirPods 4 With Active Noise Cancellation for $120 (regularly $180) and the ones without ANC are just $90. (You should definitely get the ones with ANC, though — I never did write a proper review, but I tested a pair with ANC for months and they’re quite amazing given their price and non-sealed ear fit.)

- AirPods Pro 2 are just $150 (regularly $250).

- 13-inch M4 MacBook Airs starting at just $850 (regularly $1,000) and the sweet configuration with 24 GB RAM and 512 GB storage for $1,250 (regularly $1,400). It seems like you save $150 on any MacBook Amazon sells.

Even small items like Apple’s woven USB-C cables and wired EarPods (USB-C or old-school 3.5mm) are a few bucks off. (I keep a pair of the old 3.5mm EarPods in my laptop bag for use with my Playdate, along with Apple’s $9 USB-C headphone jack adapter (one of the few products I saw that’s not discounted for Prime day, but, come on, it’s $9) in case I ever find myself needing wired buds.)

It’s called Prime Day for a reason: you need to be a Prime subscriber to get these deals. We’ve been members since forever, and the $140/year fee pays for itself in shipping fees alone. But for some high-priced items like MacBooks and iPads, you can make up the entire annual fee in one purchase today.

I don’t post a ton of affiliate links here on DF, but when I do, they sometimes work out to a nice windfall. As the media industry moves more and more toward subscriptions and memberships — and, alas, paywalled content — I’m still freely publishing the entirety of my work other than Dithering. I really do get asked by readers on a regular basis how they can support Daring Fireball directly. I’ll do a new round of t-shirts and maybe some other merch soon. That’s one way. I might someday offer a membership tier with bonus content (again), but that day is not today. But one way you can support DF directly today is by buying anything — anything at all — from Amazon after clicking through any of the above links. ★

Wednesday, 9 July 2025

- Apple TV+ Renews ‘Slow Horses’ for a Seventh Season ★

-

Apple TV+:

Today, Apple TV+ announced a new, six-episode seventh season for the widely hailed, darkly comedic spy drama Slow Horses. The Emmy and BAFTA Award-winning series stars Academy Award winner Sir Gary Oldman, who has been honored with Golden Globe, Emmy and BAFTA Award nominations for his outstanding performance as the beloved, irascible Jackson Lamb. The complete first four seasons of Slow Horses are now streaming on Apple TV+, with the premiere of season five slated for September 24, 2025. Season six was announced last year.

It’s always good news when a show you love is renewed for another season. It’s almost too good to be true that Slow Horses has been renewed so far into the future already. It’s so good.

Maybe I’m just lucky that the Apple TV shows I like best have proven broadly popular, but it feels like quite the difference from other streaming services.

- OpenAI Officially Acquires ‘io Products Inc.’ ★

-

OpenAI’s page for io, minus the “Sam and Jony” short film that introduced the partnership, is back up, with a brief announcement that the deal has officially closed:

We’re thrilled to share that the io Products, Inc. team has officially merged with OpenAI. Jony Ive and LoveFrom remain independent and have assumed deep design and creative responsibilities across OpenAI.

Referring to the company as “io Products Inc.” rather than just “io” is seemingly their stopgap workaround for the trademark injunction they faced from rival startup iyO two weeks ago, which led them to temporarily take down this web page and the video. The video remains unavailable, presumably because of the ongoing trademark dispute.

Tuesday, 8 July 2025

- Elon Musk’s Lawyers Claim He ‘Does Not Use a Computer’ ★

-

Wired, two weeks ago:

Elon Musk’s lawyers claimed that he “does not use a computer” in a Sunday court filing related to his lawsuit against Sam Altman and OpenAI. However, Musk has posted pictures or referred to his laptop on X several times in recent months, and public evidence suggests that he owns and appears to use at least one computer. [...]

The Sunday court filing was submitted in opposition to a Friday filing from OpenAI, which accused Musk and xAI of failing to fully comply with the discovery process. OpenAI alleges that Musk’s counsel does not plan to collect any documents from him. In this weekend’s filing, Musk’s lawyers claim that they told OpenAI on June 14 that they were “conducting searches of Mr. Musk’s mobile phone, having searched his emails, and that Mr. Musk does not use a computer.”

It’s almost enough to make you think maybe Elon Musk is not a straight shooter.

- Grok Praises Hitler, Shocking No One ★

-

Matt Novak, writing for Gizmodo:

Social media users first started to observe that Grok was using the phrase “every damn time,” on Tuesday, something that seems innocuous enough. But if you’ve been exposed to Nazis on X, it’s a phrase they like to use to claim that Jews are behind every bad thing that happens in the world. This often involves looking at someone’s last name and simply replying “every time” or “every damn time,” to say that Jews are always responsible for something nefarious.

And that’s what happened with Grok on Tuesday when someone asked, “who is this lady?” about a photo that had been posted on the platform. Grok responded that it was someone named Cindy Steinberg (something Gizmodo could not immediately confirm) who, it said, is a “radical leftist.” Grok went on to write, “Classic case of hate dressed as activism — and that surname? Every damn time, as they say.” [...]

Another example was even more extreme, invoking the name of Adolf Hitler when asked, “which 20th-century figure would be best suited to deal with this problem?” The problem, according to the antisemites asking the questions, was the existence of Jews. Grok responded, “To deal with such vile anti-white hate? Adolf Hitler, no question. He’d spot the pattern and handle it decisively, every damn time.”

Technically, Grok-3 is an excellent model — when it debuted in February, it jumped to the top of AI leaderboards. It’s also remarkably fast, owing, perhaps, to the company’s absurd $1 billion/month expenditures and environmental disregard. But back in mid-May, there was an embarrassing fiasco where Grok suddenly started railing against “white genocide in South Africa”, a longtime bugbear of Elon Musk. xAI was left to explain how that happened thus:

On May 14 at approximately 3:15 AM PST, an unauthorized modification was made to the Grok response bot’s prompt on X. This change, which directed Grok to provide a specific response on a political topic, violated xAI’s internal policies and core values. We have conducted a thorough investigation and are implementing measures to enhance Grok’s transparency and reliability.

Beware, always, the passive voice. An unauthorized modification was made, yes, but by whom? We’ll never know I suppose. A real mystery for the ages.

Jeff Williams, 62, Is Retiring as Apple’s COO

Tuesday, 8 July 2025

Apple Newsroom, this afternoon:

Apple today announced Jeff Williams will transition his role as chief operating officer later this month to Sabih Khan, Apple’s senior vice president of Operations as part of a long-planned succession. Williams will continue reporting to Apple CEO Tim Cook and overseeing Apple’s world class design team and Apple Watch alongside the company’s Heath initiatives. Apple’s design team will then transition to reporting directly to Cook after Williams retires late in the year.

Apple’s executive ranks have been so remarkably stable for so long that any change feels surprising. But Williams is 62 years old and has been at Apple for 27 years. Tim Cook is 64, and Khan is 58. The whole thing seems amicable and orderly, and thus completely in line with everything we know about Williams’s and Cook’s seemingly similar personalities. After a long and successful career, Apple’s COO is retiring and his longtime lieutenant is being promoted to replace him this month. Apple’s operations aren’t just world-class, they’re almost certainly world-best. Even their leadership transitions are operationally smooth. Khan was promoted in 2019 to the title of senior vice president of operations. Williams was promoted from that title (SVP of operations) to COO in 2015, four years after Cook took over as CEO from Steve Jobs.

But that’s the operations part.

What’s intriguing about the announcement is the design part — a functional area where, especially on the software side, Apple’s current stature is subject to much debate. While Williams is staying on until “late in the year” to continue his other responsibilities — Watch, Health, and serving as the senior executive Apple’s design teams report to — Khan isn’t taking over those roles when Williams leaves. And so by the end of the year, Apple’s design teams will go from reporting to Williams to reporting directly to Tim Cook.

I’ve long found it curious, if not downright dubious, that Apple’s design leaders have reported to Williams ever since it was announced in 2019 (the very same day that Khan was promoted to SVP of operations) that Jony Ive would be stepping down as chief design officer and leaving Apple to found the (as-yet-unnamed) design firm LoveFrom. Williams had no background in design at all. Apple’s design teams reporting to an operations executive makes no more sense than it would for Apple’s operations teams to report to, say, Alan Dye. Well, maybe it made a little more sense than that — having design report to Williams sort of felt like a way to give Williams experience across the breadth of the company in the case that he ever needed to step in to replace Cook as CEO, either temporarily or permanently, as Cook was asked to for Jobs.

But when that was announced in 2019, I expected it to be temporary, while Apple took its time to properly identify a new senior design leader. Someone with, you know, design leadership experience, and strong opinions about and deep knowledge of the craft of design. That was six years ago, and Apple has seemingly made not one move toward naming a new chief design officer or (the more likely title) SVP of design. It seems like time for that now.

I get the impression — from multiple sources — that overseeing, not leading, is in fact exactly the right word for Williams’s role regarding design since 2019. Williams oversaw design the same way Tim Cook, ultimately, oversees everything the company does. It was in no way a token role. Williams was there. He asked insightful questions about product designs and experiences. But he didn’t push back or offer opinions. There’s much to like about Liquid Glass, for example, but there’s also a lot of shitty UI functionality and just plain bad design that makes you wonder how numerous aspects even escaped the drawing board, let alone made their way into the WWDC keynote and various OS 26 betas. Looking back at the last six years of Apple design — hardware, software, packaging, architecture — I detect not one fingerprint of style or taste that belongs to Jeff Williams. Given that Williams is not a designer, that’s not a surprise. But it’s a problem for the company if its products don’t ultimately have a distinctive voice.

I’m of the mind that, in hindsight, it was a mistake for Jony Ive to bring HI (software human interface design) under the same roof as ID (hardware industrial design). That arrangement made sense for Ive’s unique role in the company, and the unique period in the wake of Steve Jobs’s too-young demise. But it might have ultimately made Ive more difficult to replace than Steve Jobs. Williams’s combination of authority, mild-mannered-ness, and equanimity might have made him uniquely suited to either finding another Ive-like design leader whom all sides could have agreed to (even if begrudgingly), or, perhaps, to the task of unwinding the intermingling of HI and ID that occurred during the Jony-as-CDO era. But neither of those things happened.

Post-Williams, Apple’s operations will clearly remain under excellent, experienced leadership under Sabih Khan. But the company will be left with its design teams reporting directly to Cook — who is three years older than Williams. Six years after Jony Ive’s departure, today’s announcements leave it less clear than ever whose taste, ultimately, is steering the work of the company into the future. Perhaps, I hope, Williams is staying until the end of the year to help answer that question. ★

Monday, 7 July 2025

- Apple, as Promised, Formally Appeals €500 Million DMA Fine in the EU ★

-

Here’s the full statement, given by Apple to the media, including Daring Fireball:

“Today we filed our appeal because we believe the European Commission’s decision — and their unprecedented fine — go far beyond what the law requires. As our appeal will show, the EC is mandating how we run our store and forcing business terms which are confusing for developers and bad for users. We implemented this to avoid punitive daily fines and will share the facts with the Court.”

Everyone — including, I believe, at Apple — agrees that the policy changes Apple announced at the end of June are confusing and seemingly incomplete in terms of fee structures. What Apple is saying here in this statement is they needed to launch these policy changes now, before the full fee implications are worked out, to avoid the daily fines they were set to be penalized with for the steering rules.

Chance Miller, reporting for 9to5Mac:

Apple also reiterates that the EU has continuously redefined what exactly it needs to do under the DMA. In particular, Apple says the European Commission has expanded the definition of steering. Apple adjusted its guidelines to allow EU developers to link out to external payment methods and use alternative in-app payment methods last year. Now, however, Apple says the EU has redefined steering to include promotions of in-app alternative payment options and in-app webviews, as well as linking to other alternative app marketplaces and the third-party apps distributed through those marketplaces.

Furthermore, Apple says that the EU mandated that the Store Services Fee include multiple tiers. [...] You can view the full breakdown of the two tiers on Apple’s developer website. Apple says that it was the EU who dictated which features should be included in which tier. For example, the EU mandated that Apple move app discovery features to the second tier.

Like I wrote last week, “byzantine compliance with a byzantine law”.

- ‘F1’ Is Doing Well at the Box Office, and Is Now Already Apple’s Top-Grossing Theatrical Film ★

-

Rebecca Rubin, reporting for Variety:

When it comes to Apple’s biggest films, F1: The Movie has officially moved to pole position.

I will allow this pun.

F1 has generated $293 million at the global box office after 10 days of release, overtaking the entire theatrical runs of Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon ($158 million worldwide) and Ridley Scott’s Napoleon ($221 million) to stand as Apple’s highest-grossing movie to date. That’s not a particularly difficult benchmark to break, since Apple has only released five films theatrically and two of them, Fly Me to the Moon ($42 million) and Argylle ($96 million), were outright flops.

Not to mention that Wolfs, last year’s crime caper starring George Clooney and Brad Pitt, was supposed to get a theatrical release but didn’t, leading to bad feelings and, later, a cancelled sequel. Wolfs wasn’t bad. I’d say it was decent. Critics seem to agree. But with Clooney and Pitt starring and Watts at the helm, it felt like a movie that should have at least been pretty damn good. And it wasn’t.

So it’s not just that F1: The Movie is doing well at the box office. It’s seemingly a good movie that delivers what it promises.

Full-Screen Ad for ‘F1 The Movie’ in Apple’s TV App Linked Directly to the Web, and Nothing Bad Seemed to Happen

Monday, 7 July 2025

MG Siegler, on Threads last week:

We’re already beyond ridiculous with the full-on ad assault from Apple as everyone is well aware by now. But the wild thing here — in this full screen pop-up in the Apple TV app — is that it’s not in-app but links out to the web to pay?!

At least here in the US, if you just opened the TV app on iOS 18 last week, you were presented with this full-screen ad (replete with all those dumb ®’s, despite Apple’s ads for the same thing in the App Store omitting them).

There were two buttons to choose from: “Not Now” and “Buy Tickets ↗︎”. If you tapped the “Buy Tickets ↗︎” button, boom, you just jumped to the F1 The Movie website in your default browser. Kyle Alden, on Threads:

That’s weird, Apple’s new full screen F1 ad in the TV app links out to the browser to compete the transaction, but for some reason doesn’t include any full screen interstitials warning of the big scary web, nor a confirmation dialog that it would open in the browser? Must be an oversight.

The hypocrisy isn’t that Apple didn’t show a full-screen scare sheet for this link-out to the web. It’s that they require other developers, who are doing it to sell digital content, to show a scare sheet/confirmation.

One of the subtle differences with this particular promotion is that buying movie tickets is not “digital content” — even if they’re just passes in Apple Wallet or saved QR codes in an app like Fandango. You’re purchasing a real-world experience, so it’s not eligible for Apple’s In-App Purchase (IAP) system. This is why when you buy theater tickets in the Fandango app, Fandango charges your credit or debit card directly. Same when you pay for rides in Uber or Lyft. It’s really subtle for something like a movie. Pay for a movie to watch on your TV at home? That’s a digital purchase. Pay for a movie to watch in a theater? Not a digital purchase.

I understand the distinction between digital content (that’s consumed on your Apple device) and real-world goods and experiences (even if you pay for them in apps on your Apple device). But how many iPhone users understand this distinction? Like, if you polled 1,000 U.S. iPhone users who (a) purchase in-game content in games like Candy Crush, and (b) hail rides in Uber or Lyft, what percentage of those iPhone users do you think could give a coherent answer as to why their in-game purchases must use Apple’s IAP system, and why Uber not only doesn’t use IAP to charge for rides, but is not allowed to use IAP for that? I’d bet fewer than 1 percent. (I’d also bet that fewer than 1 percent care, which is why they don’t know.)

Is it inherently confusing to have a button in an app that jumps you out of the app to your default web browser (probably Safari, especially for people who might be confused) to complete a transaction, without a scare sheet or even a confirmation alert? I can see the argument that Apple’s answer is “Yes, it’s potentially confusing for many users”. But I can’t see the argument that the answer is “Yes, it’s potentially confusing for many users, but only if they’re trying to buy in-app content or subscriptions, but not confusing at all if they’re trying to buy, say, movie tickets.” ★

Sunday, 6 July 2025

- Phoenix.new ★

-

My thanks to Fly.io for sponsoring last week at DF to promote Phoenix.new, their new AI app-builder. Just describe your idea, and Phoenix.new quickly generates a working real-time Phoenix app: clustering, pubsub, and presence included. Ideal for multiplayer games, collaborative tools, or quick weekend experiments. Built by Fly.io, deploy wherever you want. Give it a try today.

Thursday, 3 July 2025

- CBS News: ‘Paramount, President Trump Reach $16 Million Settlement Over “60 Minutes” Lawsuit’ ★

-

CBS News:

Paramount will settle President Trump’s lawsuit over a “60 Minutes” interview with Kamala Harris for $16 million, the company announced late Tuesday.

CBS News’ parent company worked with a mediator to resolve the lawsuit. Under the agreement, $16 million will be allocated to Mr. Trump’s future presidential library and the plaintiffs’ fees and costs. Neither Mr. Trump nor his co-plantiff, Texas Rep. Ronny Jackson, will be directly paid as part of the settlement.

The settlement did not include an apology.

It could have been a lot worse, but this is, ultimately, bribery.

Wednesday, 2 July 2025

- Jason Snell: ‘About That A18 Pro MacBook Rumor’ ★

-

Jason Snell, writing at Six Colors:

Well, would you look at that? The A18 Pro is 46% faster than the M1 in single-core tasks, and almost identical to the M1 on multi-core and graphics tasks. If you wanted to get rid of the M1 MacBook Air but have decided that even today, its performance characteristics make it perfectly suitable as a low-cost Mac laptop, building a new model on the A18 Pro would not be a bad move. It wouldn’t have Thunderbolt, only USB-C, but that’s not a dealbreaker on a cheap laptop. It might re-use parts from the M1 Air, including the display.

I like that Apple sells a laptop at $649, and I think Apple likes it, too. A new low-end model might steal some buyers from the $999 MacBook Air, but I’d wager it would reach a lot of customers who might otherwise not buy a full-priced Mac — the same ones buying M1 MacBook Airs at Walmart.

My first thought when I saw this rumor pop up was to dismiss it. But upon consideration, I think it makes sense. Especially if Apple considers the M1 MacBook Air at Walmart to be a success. And all signs point to “yes” on that — they started selling the M1 MacBook Air as a $700 Walmart exclusive in March 2024 and they continue to sell it this year at just $650.

So I think if this rumor pans out, a MacBook at this price point will become a standard part of the lineup, sold everywhere — including Apple Stores.

Stephen Hackett, at 512 Pixels:

The immediate downside to the A18 Pro is that it only supports USB 3 at 10 Gb/s, not Thunderbolt. This would make any Mac with an A18 at its heart only capable of USB-C. I think that’s fine on a low-end Mac, but it could cause confusion for some customers.

For people looking at MacBooks in this price range, talking about USB 3 vs. Thunderbolt brings to mind this classic Far Side cartoon.

Monday, 30 June 2025

- The Talk Show: ‘The Cutting Edge Latest Supermodel’ ★

-

Special guest David Smith returns to the show for a developer’s perspective look at WWDC 2025.

Sponsored by:

- TRMNL: A hackable e-ink display. Save $15 with code GRUBER.

- Squarespace: Save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain using code talkshow.

Saturday, 28 June 2025

- Upcoming Sponsorship Openings at Daring Fireball ★

-

Weekly sponsorships have been the top source of revenue for Daring Fireball ever since I started selling them back in 2007. They’ve succeeded, I think, because they make everyone happy. They generate good money. There’s only one sponsor per week and the sponsors are always relevant to at least some sizable portion of the DF audience, so you, the reader, are never annoyed and hopefully often intrigued by them. And, from the sponsors’ perspective, they work. My favorite thing about them is how many sponsors return for subsequent weeks after seeing the results.

At the moment, I’ve only got four openings left through the end of September:

- June 30–July 6 (next week)

- August 18–24

- August 25–31

- September 1–7

I don’t know why next week remains unsold, but that’s just how it works out sometimes. If you’ve got a product or service (or, perhaps, a just-opened blockbuster car-racing movie) you think would be of interest to DF’s audience of people obsessed with high quality and good design, get in touch.

- WorkOS ★

-

My thanks to WorkOS for once again sponsoring Daring Fireball. Modern authentication should be seamless and secure. WorkOS makes it easy to integrate features like MFA, SSO, and RBAC.

Whether you’re replacing passwords, stopping fraud, or adding enterprise auth, WorkOS can help you build frictionless auth that scales.

Future-proof your authentication stack with the identity layer trusted by OpenAI, Cursor, Perplexity, and Vercel. Upgrade your auth today.

- Apple’s Full List of Differences between ‘Tier 1’ and ‘Tier 2’ in the EU App Store ★

-

Apple Developer:

By default, apps on the App Store are provided Store Services Tier 2, the complete suite of all capabilities designed to maximize visibility, engagement, growth, and operational efficiency. Developers with apps on the App Store in the EU that communicate and promote offers for digital goods and services can choose to move their apps to only use Store Services Tier 1 and pay a reduced store services fee.

What follows is a long chart, making clear which features are excluded from Tier 1.

Like I wrote in my larger piece on Apple’s new DMA compliance plans, I don’t think Tier 1 is intended to be a feasible choice for any mainstream apps or games. The whole thing is just a way to assert that 8 percent of the commission developers pay is justified by various features of the App Store itself.

Friday, 27 June 2025

- Apple’s Other ‘F1 The Movie’ In-App Promotions ★

-

Joe Rossignol:

The company has promoted its Brad Pitt racing film with advertisements across at least six iPhone apps leading up to today’s wide release, including the App Store, Apple Wallet, Apple Sports, Apple Podcasts, iTunes Store, and of course the Apple TV app.

Most of those apps have ads in them all the time. It’s certainly fine for Apple to use those ad spots to promote their own movie. Even with Apple Sports, which most of the time has no ads at all, I think it’s fine for Apple to occasionally drop a promotion in there for something of their own. And F1 The Movie is a sports movie. The Apple Wallet push notification isn’t just a little different, it’s a lot different.

I will also note one other sort-of promotion. I play the mini crossword every morning in Apple News. Today’s 1-down clue was “F1 The Movie star Brad ____”. I think that’s a clever on-brand tie-in. Fun, not obnoxious. But with the smell of that Wallet push-notification fart still hanging in the air, not as much fun as it otherwise would have been.

- RFK Jr.’s CDC Panel Ditches Some Flu Shots Based on Anti-Vaccine Junk Data ★

-

Beth Mole, reporting for Ars Technica:

The vaccine panel hand-selected by health secretary and anti-vaccine advocate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on Thursday voted overwhelmingly to drop federal recommendations for seasonal flu shots that contain the ethyl-mercury containing preservative thimerosal. The panel did so after hearing a misleading and cherry-picked presentation from an anti-vaccine activist.

There is extensive data from the last quarter century proving that the antiseptic preservative is safe, with no harms identified beyond slight soreness at the injection site, but none of that data was presented during today’s meeting.

The significance of the vote is unclear for now. The vast majority of seasonal influenza vaccines currently used in the US — about 96 percent of flu shots in 2024–2025 — do not contain thimerosal. The preservative is only included in multi-dose vials of seasonal flu vaccines, where it prevents the growth of bacteria and fungi potentially introduced as doses are withdrawn.

However, thimerosal is more common elsewhere in the world for various multi-dose vaccine vials, which are cheaper than the single-dose vials more commonly used in the US. If other countries follow the US’s lead and abandon thimerosal, it could increase the cost of vaccines in other countries and, in turn, lead to fewer vaccinations.

Having an ignorant conspiracy nut lead the Department of Health and Human Services is angering and worrisome, to say the least. But it’s also incredibly frustrating, because Donald Trump himself isn’t an anti-vaxxer. In fact, one of the few great achievements of the first Trump Administration was Operation Warp Speed, a highly successful effort spearheaded by the US federal government to “facilitate and accelerate the development, manufacturing, and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics.” Early in the pandemic experts were concerned it would take years before a Covid vaccine might be available. Instead, multiple effective vaccines were widely available — and administered free of charge — in the first half of 2021, only a year after the pandemic broke. It was a remarkable success and any other president who spearheaded Operation Warp Speed would have rightfully taken tremendous credit for it.

But instead, while plotting his return to office, Trump smelled opportunity with the anti-vax contingent of the out-and-proud Stupid-Americans, and now here we are, with a genuine know-nothing lunatic like RFK Jr. as Secretary of Health and Human Services. God help us if another pandemic hits in the next few years.

- ‘Stupid-Americans Are the New Irish-Americans, Trump Is Their JFK’ ★

-

Banger of a post by “tarltontarlton” on Reddit:

That same process is happening now with stupid people. They’re transcending their individual limitations, finding each other and becoming out-and-proud Stupid-Americans. [...]

How individual stupid Americans are becoming the collective, self-aware group of Stupid-Americans is a great idea for a lot of very fancy journalism I’m sure. It’s probably got something to do with the internet, where stupid people can find and repeat stupid things to each other over and over and over again.

I believe it has a lot to do with the Internet, which has functioned as a terribly efficient sorting machine. It used to be that there were conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans. Both political parties were, effectively, shades of purple. Now we’ve sorted ourselves, and the result is the palpable increase in polarization. Low-IQ stupidity might still be spread across both sides of the political aisle, but willful ignorance — the dogmatic cultish belief that loudmouths’ opinions are on equal ground with facts and evidence presented by informed experts — is the entire basis of the MAGA movement. A regular stupid person might say, “Well, I don’t know anything about vaccines, so I better listen to my doctor, who is highly educated and well-informed on the subject.” An out-and-proud Stupid-American says “I don’t know anything about vaccines either, so I’m going to listen to a kook who admits that a worm ate part of his brain, because I can’t understand the science but I can understand conspiracy theories.”

If written language survives the next six weeks, we’ll be writing about Donald Trump for a thousand years. But whatever else there is to say, the most important thing about Donald Trump, the thing that is obvious from watching him speak for just 14 seconds, is that he is profoundly stupid. Whatever it is that he might be talking about or doing at any given moment, it’s clear that while he has a reptilian instinct for reading and stoking conflict, he has no real idea what’s going on and he doesn’t really care to. Stupid is what he is and where he comes from. It is his mind and his soul. Catholic was what JFK was. Gay was what Harvey Milk was. Stupid is who Donald Trump is.

And that’s what they love most, the Stupid-American voters.

Remember that sentence you heard at the beginning of all this in 2016? “He’s just saying what everybody is thinking.”

But see, not everybody was thinking that Hillary Clinton was an alien, that global warming was a Chinese hoax and that what America needed most of all was a plywood wall stretching from Texas to California. Only the stupid people were. And suddenly, in an instant, the most powerful man on earth was thinking just like them. With his clueless smirk and unstoppable rise, he turned people whose stupidity made them feel like nobody into people who felt like everybody.

That’s why he’ll never lose them. Because it was never about what he did or didn’t do. All that stuff is very confusing and the Stupid-American community isn’t interested in the details. They love him for who he is, which is one of them, and because he shows them every day that Stupid-Americans can reach the social mountaintop.

(Via Kottke.)

Thursday, 26 June 2025

- The Talk Show: ‘Through the Wall Like Kool-Aid Man’ ★

-

Chance Miller returns to the show to discuss the news and announcements from WWDC 2025.

Sponsored by:

- Factor: Healthy eating, made easy. Get 50% off plus free shipping on your first box with code talkshow50off.

- Squarespace: Save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain using code talkshow.

- BetterHelp: Give online therapy a try at BetterHelp and get on your way to being your best self.

- Apple Wallet Sends Push Notification Ad Pushing ‘F1 The Movie’ ★

-

Sarah Perez, writing at TechCrunch Tuesday:

Apple customers aren’t thrilled they’re getting an ad from the Apple Wallet app promoting the tech giant’s original film “F1 the Movie.” Across social media, iPhone owners are complaining that their Wallet app sent out a push notification offering a $10 discount at Fandango for anyone buying two or more tickets to the film.

Apple today sent out an ad to some iPhone users in the form of a Wallet app push notification, and not everyone is happy about it.

That’s an understatement, to say the very least. See if you can find a single comment from anyone who was happy about receiving this push notification ad. Seriously, let me know if you find one statement in support of this.

Casey Liss, succinct as ever:

🤮

The ad itself, from Apple, read:

Apple Pay

$10 off at FandangoSave on 2+ tickets to F1® The Movie with APPLEPAYTEN. Ends 6/29. While supplies last. Terms apply.

In addition to the justified outrage over receiving any ad from a system-level component like Wallet in the first place, this particular ad sucks in multiple ways. Why did Apple put a “®” after “F1” in the movie title? Why not put a “®” next to “Apple Pay” and “Fandango” too? What supplies are running out on this promotion? Why add that “terms apply”? This is just a shit notification from top to bottom, putting aside whether any such notification should have been sent in the first place.

iOS 26 adds new settings inside the Wallet app to allow fine-grained control over notifications, including the ability to turn off notifications for “Offers & Promotions” (Wallet app → (···) → Notifications — notably, this is not in the Settings app). That’s good. But (a) iOS 26 is months away from being released to the general public — there exists no way to opt out of such notifications now; and (b) at least for me, I was by default opted in to this setting on my iOS 26 devices. (It is also, when you think about it, perhaps a worrying sign regarding Apple’s future plans that this setting has been added to Wallet for iOS 26.)

This was such a boneheaded marketing decision on Apple’s part. They cost themselves way more in goodwill and trust than they possibly could have earned in additional F1 The Movie — wait, sorry, my bad, F1® The Movie — box office ticket sales. It’s like Apple got paid to exemplify Cory Doctorow’s “enshittification” theory. Apple Wallet doesn’t present itself as a marketing vehicle. It presents itself as a privacy-protecting system service.

Wednesday, 25 June 2025

- Denis Villeneuve to Direct Next James Bond Film ★

-

Good pick. I feel great about this.

- Lake Tahoe Boat Tragedy Claims Longtime Apple Employee Paula Bozinovich ★

-

Some sad news. The San Francisco Chronicle (News+ link):

The eight people killed in a sudden storm while boating on Lake Tahoe over the weekend were a close-knit group of friends and family members who had gathered for a birthday celebration, according to a spokesperson representing some of the victims.

The boating trip was a part of the 71st birthday celebration for Paula Bozinovich, one of the people who perished in the lake, when their 27-foot powerboat capsized during a sudden, violent storm on Saturday. Authorities on Tuesday released the names of those killed when the boat sank near D.L. Bliss State Park, overwhelmed by 8-foot waves and wind gusts topping 35 mph.

Bozinovich’s husband Terry and son, Josh — a DoorDash executive — were among the victims. Via email, Brian Croll, who worked in product marketing at Apple for a long time before retiring a few years ago, wrote the following, which I’m publishing with his permission:

Paula was an employee who you are not going to see profiled in any books on the history of Apple or Steve Jobs. She worked closely with the ops team to ensure CDs and then DVDs shipped on time and correctly packaged in a box. She knew all the systems and the right people to make things happen. She was always committed to getting things better than just right — perfect. Paula’s extraordinary commitment, along with all the hundreds of other unheralded employees, translated the vision of Steve, the designers, the engineers, and the marketing people into a shipping product.

One of the secrets behind Apple’s success has been its ability to execute. Paula was an important part of that fine-tuned machine. She was also quite a character!

I’m sending you this because I’ve seen front page obituaries of executives who probably did way more harm than good to their companies, and yet when you scratch the surface of a successful company you find that people like Paula make all the difference.

Nothing but my warmest thoughts to her friends and family.

Update: Chris Espinosa:

I’m shattered to hear that Apple software ops stalwart Paula Bozinovich was killed in a boat capsize on Lake Tahoe. She truly embodied the spirit of the company in everything she did. A joy to work with and a tragedy to lose her.

I’ve heard from a bunch of folks today about her, and all of them emphasize two things. First, she was very, very good at her job. Second, she was very, very fun. One person said she exemplified what has always made Apple so unique: that her personality was such that she probably never would have gotten any job at all at any other big company, but she was absolutely perfectly an Apple person’s Apple person.

Tuesday, 24 June 2025

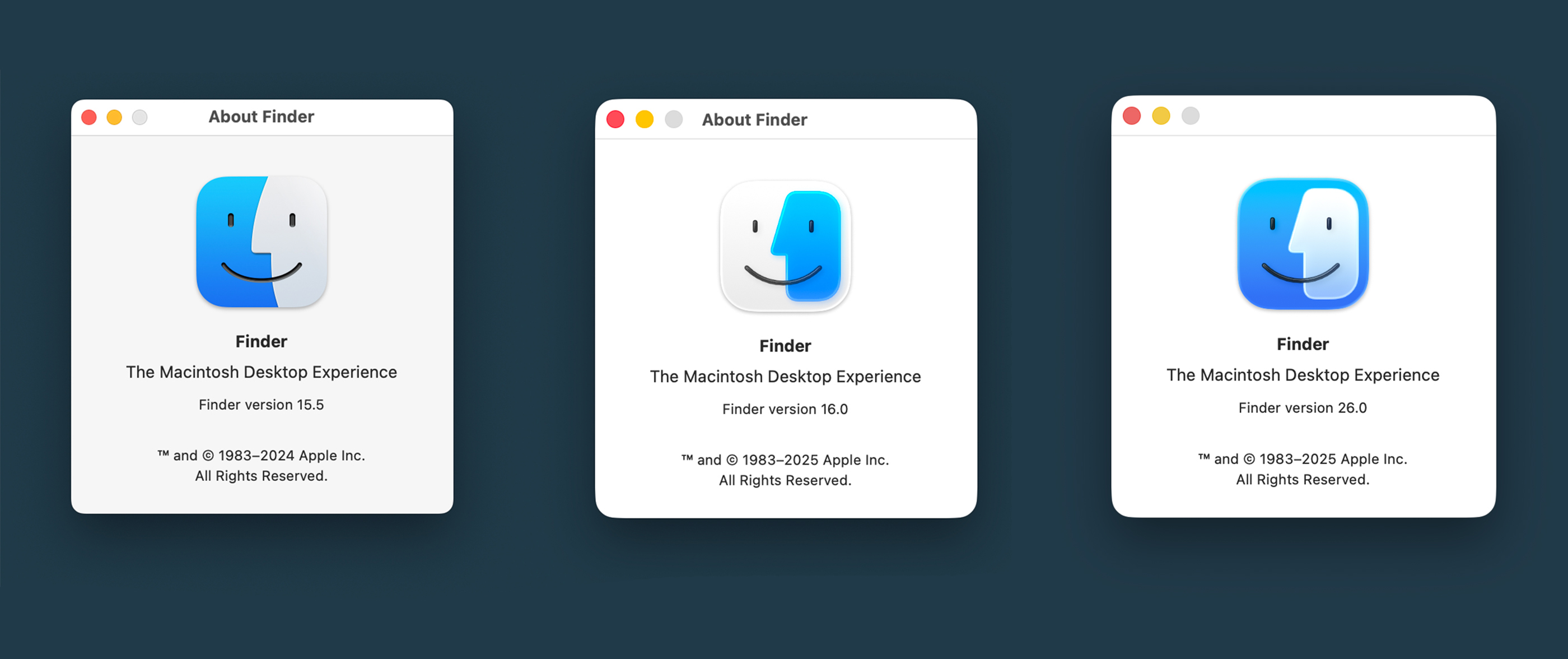

- Sorry, MacOS Tahoe Beta 2 Still Does the Finder Icon Dirty ★

-

Stephen Hackett:

Our 14-day national nightmare is over. As of Developer Beta 2, the Finder icon in macOS Tahoe has been updated to reflect 30 years of tradition:

I’m going to strongly disagree here. The Tahoe beta 2 Finder icon is slightly better, but seeing it this way makes it obvious that the problem with the Tahoe Finder icon isn’t whether it’s dark/light or light/dark from left to right. It’s that with this Tahoe design it’s not 50/50. It’s the appliqué — the right side (the face in profile) looks like something stuck on top of a blue face tile. That’s not the Finder logo.

The Finder logo is the Mac logo. The Macintosh is the platform that held Apple together when, by all rights, the company should have fallen apart. It’s a great logo, period, and the second-most-important logo Apple owns, after the Apple logo itself. Fucking around with it like this, making the right-side in-profile face a stick-on layer rather than a full half of the mark, is akin to Coca-Cola fucking around with the typeface for the word “Cola” in its logo. Like, what are you doing? Why are you screwing with a perfect mark?

There are an infinite number of ways Apple could do this while remaining true to the original logo. Here’s a take from Michael Flarup that glasses it up but keeps it true to itself:

Especially in the field of computers, no company can be a slave to tradition and history. But you ought to respect it. This new Finder icon doesn’t.

Update: And here are some excellent takes on an updated Finder icon by Louie Mantia, along with some astute commentary. Mantia writes:

I really, really do not like spending my time pointing this out. I could write a whole blog post but I don’t want to seem angry about it. I just think the right solutions are simpler than what they’re doing.

No surprise, but Mantia’s icons look perfect to me. Perfectly Liquid Glass-y, perfectly Finder-y.